This is what we have been working on

هذا ما نقوم بالعمل عليه

“How to work together”

Or how do we live or survive together? Or how to be interdependent?

كيف نعمل معًا؟

أو كيف نعيش

أو ننجو معًا؟

أو كيف نكون مترابطين؟

In late 2019 and 2020, at the outset of the Covid-19

pandemic, several cultural institutions in Palestine were on the brink of

closure due to insufficient funds. This reality was compounded with the fact

that many people lost jobs during the pandemic, not merely in the field of arts

and culture or other organizations working in civil society but in the wider

economic ecosystems that typically thrive alongside these institutions.

The Question of Funding collective was born out of the first two assemblies at the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center and focused on questions that directly affected the livelihood of entire sectors and people.

Held in 2019, our first assembly was entitled "Funding: How do we rethink the economic crisis from a cultural point of view?". It gathered a number of individuals and groups from across Palestine and yielded a heap of material, from testimonials and interventions, to glossaries and other inputs from different participants across various sectors and localities. We centered the meeting on one question: what does funding mean to you? As a result, we divided the answers we received from the participants into different themes and consolidated all the ensuing discussions with the question of “How to work together”, or how to approach these themes collectively. The themes but also vectors of research and discussion allowed us to excavate what we already knew and didn’t know yet, what problems others were facing with funding, and what possible solutions we could work on together. Most importantly, we wanted to ask how we can create a structure that would be sustainable, to create and disseminate knowledge, and expand beyond the geography of Ramallah.

To put it simply, we wanted to see how we could rally ourselves to try and find ways to work collectively, not just to assuage present and future crises but to really seek practicable models for economic interdependence and knowledge production in Palestine. Our ongoing work on Dayra, which requires a sustained engagement with the localities in Palestine, puts into practice a model that best reflects the foundational questions that surfaced from the large assemblies.

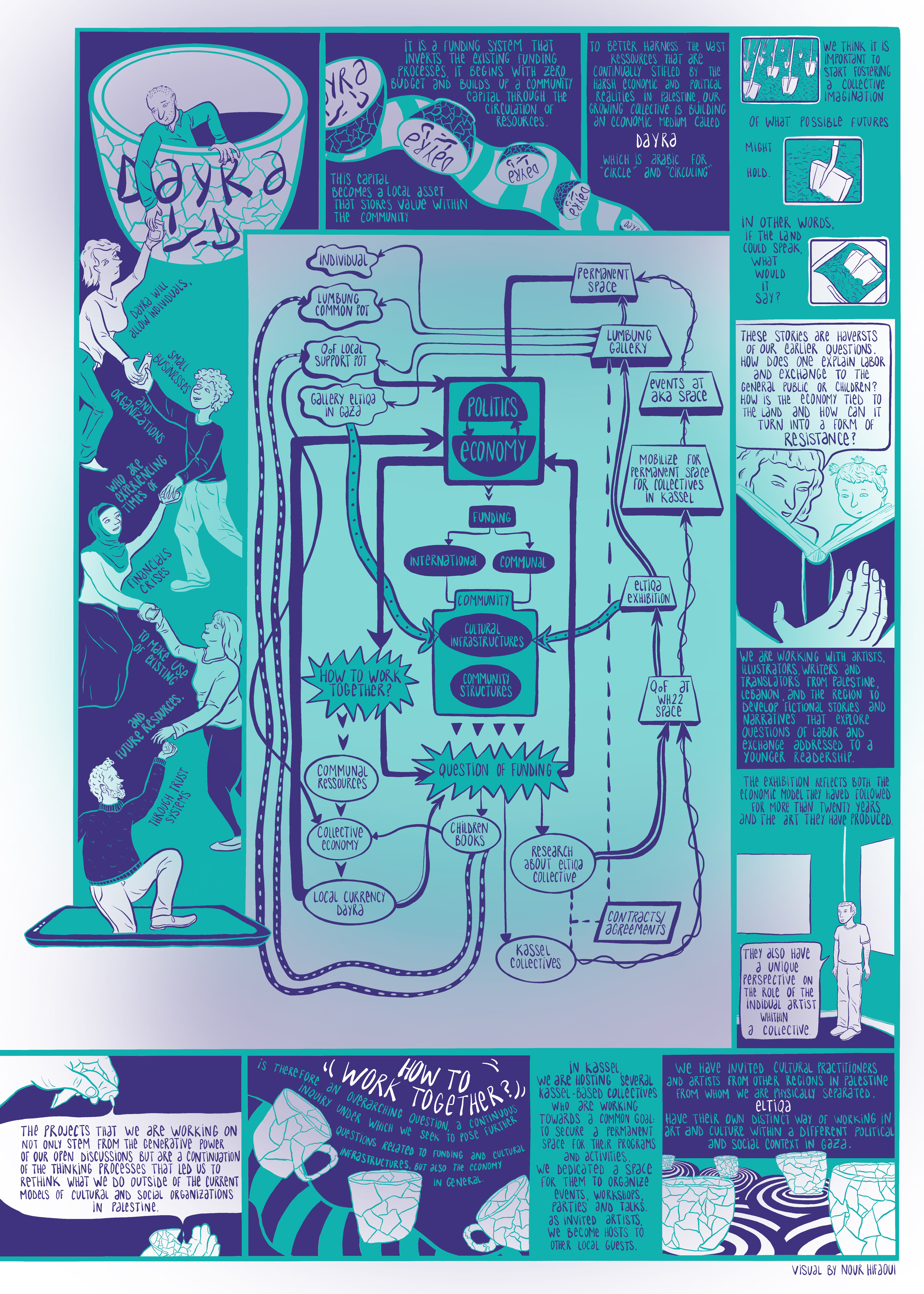

In essence, all the projects that we work on not only stem from the generative power of these open discussions but are a continuation of the thinking processes that led us to rethink what we do outside of the current models of cultural and social organizations in Palestine.

“How to work together?” is a comprehensive question under which we sought to pose further issues related to funding and cultural infrastructures, but also the economy in general.

The Question of Funding collective was born out of the first two assemblies at the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center and focused on questions that directly affected the livelihood of entire sectors and people.

Held in 2019, our first assembly was entitled "Funding: How do we rethink the economic crisis from a cultural point of view?". It gathered a number of individuals and groups from across Palestine and yielded a heap of material, from testimonials and interventions, to glossaries and other inputs from different participants across various sectors and localities. We centered the meeting on one question: what does funding mean to you? As a result, we divided the answers we received from the participants into different themes and consolidated all the ensuing discussions with the question of “How to work together”, or how to approach these themes collectively. The themes but also vectors of research and discussion allowed us to excavate what we already knew and didn’t know yet, what problems others were facing with funding, and what possible solutions we could work on together. Most importantly, we wanted to ask how we can create a structure that would be sustainable, to create and disseminate knowledge, and expand beyond the geography of Ramallah.

To put it simply, we wanted to see how we could rally ourselves to try and find ways to work collectively, not just to assuage present and future crises but to really seek practicable models for economic interdependence and knowledge production in Palestine. Our ongoing work on Dayra, which requires a sustained engagement with the localities in Palestine, puts into practice a model that best reflects the foundational questions that surfaced from the large assemblies.

In essence, all the projects that we work on not only stem from the generative power of these open discussions but are a continuation of the thinking processes that led us to rethink what we do outside of the current models of cultural and social organizations in Palestine.

“How to work together?” is a comprehensive question under which we sought to pose further issues related to funding and cultural infrastructures, but also the economy in general.

في أواخر

سنتي ٢٠١٩ و٢٠٢٠، في بداية تفشي جائحة كوفيد -١٩، كانت العديد من المؤسسات

الثقافية في فلسطين على وشك الإغلاق بسبب الشحّ في الأموال.

تضافر هذا الواقع مع حقيقة أن العديد من الناس فقدوا وظائفهم أثناء الوباء، ليس في

ميدان الفنون والثقافة أو المنظمات الأخرى العاملة في المجتمع المدني فحسب، وإنما

في النظم الاقتصادية الأوسع التي تزدهر عادةً جنبًا إلى جنب مع هذه المؤسسات.

ولدت مجموعة مسألة التمويل من أول اجتماعيَن في مركز خليل السكاكيني الثقافي وركزت على الأسئلة التي أثرت بشكل مباشر على سبل عيش قطاعات وأفراد بأكملها.

عُقد اجتماعنا الأول في عام ٢٠١٩، وحمل عنوان "التمويل: كيف نعيد التفكير في الأزمة الاقتصادية من وجهة نظر ثقافية؟". ضمّ ثلّةً من الأفراد والجماعات من جميع أنحاء فلسطين وانبثقت منه كومة من المواد، منوعة بين الشهادات والمداخلات، إلى المسارد والمدخلات الأخرى من مختلف المشاركين في شتّى القطاعات والمجتمعات المحليّة. ركزنا الاجتماع على سؤال يتيم: ماذا يعني التمويل بالنسبة لك؟ ونتيجة لذلك، قمنا بتقسيم الإجابات التي تلقيناها من المشاركين إلى موضوعات مختلفة ودمجنا كلّ المناقشات التي تلت ذلك بسؤال "كيف نعمل معاً؟"، أو كيفية التعامل مع هذه الموضوعات بشكل جماعي. سمحت لنا الموضوعات ناهيك عن موجهات البحث والمناقشة بالتنقيب عما كنا نعرفه بالفعل وما لم نعرفه حتى الآن، وما هي المشكلات التي يواجهها الآخرون في التمويل، وما هي الحلول الممكنة التي بمقدورنا العمل عليها معاً. والأهم من ذلك، أردنا أن نسأل كيف يمكننا إنشاء بنية مستدامة، لخلق ونشر المعرفة، والتوسع أبعد من جغرافياة رام الله.

أردنا ببساطة أن نرى كيف يمكننا حشد طاقاتنا لمحاولة إيجاد طرق للعمل الجماعي، ليس لتهدئة الأزمات الحالية والمستقبلية فحسب، وإنما أيضًا للبحث عن نماذج عملية للترابط الاقتصادي وإنتاج المعرفة في فلسطين. إنّ عملنا المستمر في دايرا، والذي يتطلب مشاركة مستدامة مع التجمعات المحلية في فلسطين، يضع قيد التنفيذ نموذجاً يعكس على أكمل وجه الأسئلة التأسيسية التي ظهرت للعيان من التجمعات الكبيرة.

في الجوهر، لا تنبع كلّ المشاريع التي نعمل عليها من القوة الخلّاقة لهذه المناقشات المفتوحة فحسب، بل هي استمرار لعمليات التفكير التي دفعتنا إلى إعادة النظر فيما نقوم به خارج النماذج الحالية للمنظمات الثقافية والاجتماعية في فلسطين.

"كيف نعمل معاً؟" هو سؤال شامل سعينا من خلاله إلى طرح المزيد من القضايا المتعلقة بالتمويل والبنى التحتية الثقافية، ولكن أيضًا بالاقتصاد بشكل عام.

The QoF in documenta fifteen

Or how do we work between localities?

مسألة التمويل في دوكيومنتا ١٥

أو كيف نعمل في المجتمعات المحلية؟

Since we were a very young collective when documenta approached us to take part in its fifteenth edition and despite our initial hesitations to commit to such an endeavor, the projects we presented there reflect both the conceptual and theoretical vectors that emerged from our ongoing debates and discussions on the question of funding, economic infrastructures, as well as knowledge production.

Our presence in documenta fifteen took the form of four different aspects that were activated in various ways both locally in Kassel and beyond the framework of the 100 days of the exhibition.

The lumbung, which brought together hundreds of collectives and thousands of individuals both before and during documenta fifteen, proposed a unique structure within which we deployed our processes, invited friends and collaborators, and thought and worked together around issues at the core of our processes, invited friends and collaborators, and thought and worked together around issues at the core of our practice.

بما أننا كنّا مجموعة شابّة للغاية عندما دُعينا للمشاركة في النسخة الخامسة عشرة من Documenta 15، وعلى الرغم من ترددنا في البداية في الالتزام بهذا المسعى، فإن المشاريع التي قدّمناها هناك تعكس مجموعة من الموجّهات المفاهيمية والنظرية التي انبثقت من مناظراتنا ومناقشاتنا المستمرة حول مسألة التمويل، والبنى التحتية الاقتصادية، ناهيك عن إنتاج المعرفة.

اتّخذَ تواجدُنا في دوكيومنتا ١٥ هيئة أربعة جوانب متنوعة جرى تفعيلها بطرق مختلفة محليّاً في كاسل وتخطّت إطار مئة يوم من المعرض.

اقترحت لومبونغ التي جمعت مئات المجموعات والآلاف من الأفراد قبل وأثناء دوكيومنتا ١٥ هيكلًا فريدًا وزّعنا فيه عملياتنا ودعونا الأصدقاء والمتعاونين، وفكّرنا وعملنا معاً حول المسائل التي تقع في صميم ممارستنا.

Poster by Nour Hifaoui

Welcome to Aka

Or how to connect to a context?

As a collective in the lumbung and in documenta fifteen, we wanted to work against the usual patterns imposed by big artistic institutions and biennials that typically invite artists and cultural workers to produce works, exhibit them and swiftly leave without having engaged the city and its residents.

In the spirit of the lumbung, we opened one of our spaces in documenta fifteen to other local collectives who were working on their diverse projects and within their own communities. As such, we engaged in long discussions with several Kassel-based collectives and organizations who shared a common goal: to secure a permanent space for their programs and activities. In WH22, the abandoned building we shared with other documenta fifteen artists, they came together to create aka, a decentralized network of self-organizing and grassroots collectives and open space for concerts, workshops, performances, exhibitions, discussions, and more.

As invited artists, we become hosts to other local guests. They host their activities in our space and we use their space to host our own. The connection with aka extends the map of relations, almost like ripples in a pond that widen the circles of individuals, ideas, and potentials.

As invited artists, we became hosts to other local guests. They host their activities in our space and we used their space to host our own. The connection with aka extends the map of relations, almost like ripples in a pond that widen the circles of individuals, ideas, and potentials.

Since December 2022, a few months after documenta fifteen ended, aka have officially become the tenants of WH22, in the hope that they will use and rent the rest of the area in Spring 2023. While the city of Kassel will provide financial support, aka will remain independent and decide how best to use the space and its surroundings. After some time to reflect and develop, aka still hopes that their collective structure will be able to buy WH22 collectively.

أهلا بكم في aka

أو كيف تتصلون بسياق ما؟

أردنا كمجموعة مشاركة في اللومبونغ وفي دوكيومنتا ١٥ العملَ ضد الأنماط المعتادة التي تفرضها المؤسسات الفنية الكبيرة والبيناليات التي عادةً ما تدعو الفنانين والعاملين في المجال الثقافي لإنتاج الأعمال وعرضها والمغادرة على جناح السرعة دون إشراك المدينة وسكانها.

بروحية مستلهمة من اللومبونغ، فتحنا واحدة من مساحاتنا للمجموعات المحلية الأخرى التي كانت تعمل على مشاريعها المتنوعة وفي قلب مجتمعاتها الخاصة. شاركنا على هذا النحو في نقاشات طويلة مع العديد من التجمعات والمنظمات التي تتخذ من مدينة كاسل مقراً لها والتي تتقاسم هدفاً مشترَكاً: تأمين مساحة دائمة لبرامجها وأنشطتها. في WH22 المبنى المهجور الذي تقاسمناه مع خمسة عشر فنانًا آخرين من دوكيومنتا ١٥، اجتمع الكلّ لخلق aka، وهي عبارة عن شبكة لامركزية من التنظيم الذاتي والقواعد الشعبية ومساحة مفتوحة للحفلات الموسيقية وورش العمل والعروض الفنّية والمعارض والنقاشات وما يتعدّاها.

بصفتنا فنانين مدعوين، غدونا مضيفِين لضيوف محليين آخرين، كان أن استضافوا أنشطتهم في مساحتنا واستخدمنا مساحتهم لاستضافة أنشطتنا. يمتد الارتباط بـ "aka" إلى خريطة العلاقات بأسرها، وهو أشبه بموجات في بركة توسّع دوائر الأفراد والأفكار والإمكانيات.

منذ كانون الأول (ديسمبر) ٢٠٢٢، أي بعد بضعة أشهر من انتهاء دوكيومنتا ١٥، أصبحت أكى رسميًا هي المستأجِرة لـWH22، على أمل أن تستخدم وتستأجر ما تبقّى من المساحة في ربيع ٢٠٢٣. بينما تتكفل مدينة كاسل بالدعم المالي، ستبقى أكى مستقلة وتبحث في اقرار أفضل السبل لاستخدام المساحة والمناطق المحيطة بها. بعد قليل من الوقت في التفكير والتطوير، لا تزال aka تأمل أن يتمكن هيكلها الجماعي من شراء WH22 بشكل تشاركي.

The 7 principles of aka are:

aka is a decentralized network.

a collective of collectives from Kassel.

aka is a medium.

we understand aka as a practice and a tool in order to establish a solidarity network among local communities.

aka is a space towards a space.

there is a need for spaces for grassroots movements in Kassel. aka uses WH22 to actively establish such a space in the city.

aka is lumbung.

aka is based on the principle of communality: pooled collective ideas, knowledge, funding and other shareable resources.

aka is based on (un)common grounds.

how do we practice our diversity and our (dis)agreements?

aka is an economy.

a solidarity economy which benefits collectives, individuals and bigger communities. It’s based on non-commercial principles and collective decision making.

aka is a host. aka is a guest.

a host and a guest. a guest and a host. QoF invites aka, aka invites QoF.

aka is a decentralized network.

a collective of collectives from Kassel.

aka is a medium.

we understand aka as a practice and a tool in order to establish a solidarity network among local communities.

aka is a space towards a space.

there is a need for spaces for grassroots movements in Kassel. aka uses WH22 to actively establish such a space in the city.

aka is lumbung.

aka is based on the principle of communality: pooled collective ideas, knowledge, funding and other shareable resources.

aka is based on (un)common grounds.

how do we practice our diversity and our (dis)agreements?

aka is an economy.

a solidarity economy which benefits collectives, individuals and bigger communities. It’s based on non-commercial principles and collective decision making.

aka is a host. aka is a guest.

a host and a guest. a guest and a host. QoF invites aka, aka invites QoF.

المبادئ السبعة لـ أكى هي:

أكى شبكة لامركزية.

تشكيل جماعي من تشكيلات جماعية في كاسل.

أكى وسيط.

نفهم aka كممارسة وأداة في سبيل خلق شبكة تضامن بين المجتمعات المحلية.

أكى فضاء نحو فضاء.

ثمة حاجة لمساحات مخصّصة لتحركات القواعد الشعبية في كاسل. تستخدم أكى WH22 لإنشاء مثل هذه المساحة بفعالية في المدينة.

أكى هي لومبونغ

ترتكز أكى على مبدأ الجماعة المشترَكة: الأفكار الجماعية المؤتلفة والمعرفة والتمويل والموارد الأخرى القابلة للمشاركة.

ترتكز أكى على أسس (غير) مشتركة.

كيف نمارس تنوّعنا و(عدم) وئامنا؟

أكى هي نوع من الاقتصاد.

اقتصاد تضامني تستفيد منه الجماعات والأفراد والمجتمعات الأكبر. إقتصاد قائم على المبادئ غير التجارية واتخاذ القرارات الجماعية.

ترتكز أكى على مبدأ الجماعة المشترَكة: الأفكار الجماعية المؤتلفة والمعرفة والتمويل والموارد الأخرى القابلة للمشاركة.

ترتكز أكى على أسس (غير) مشتركة.

كيف نمارس تنوّعنا و(عدم) وئامنا؟

أكى هي نوع من الاقتصاد.

اقتصاد تضامني تستفيد منه الجماعات والأفراد والمجتمعات الأكبر. إقتصاد قائم على المبادئ غير التجارية واتخاذ القرارات الجماعية.

أكى مُضيف. أكى ضيف.

مُضيف وضيف. ضيف ومُضيف. مسألة التمويل تدعو أكى و أكى أيضًا تدعو مسألة التمويل.

Jam on Jam on Jam on Jam

Collectivity of collective sounds or how to jam together?

During documenta fifteen’s opening week, we invited the study group JamOnJamOnJamOnJam, which is composed of artists from the Global South and based in Amsterdam. JamOnJamOnJamOnJam is a series of jamming/gathering through sonic exchange by several residents on Radio Alhara. It started in the middle of lockdown in 2020 when the artists’ shared acoustic space became less accessible, this activity aimed to share the joy of jamming with friends and family beyond the acoustic space where the jamming takes place. Much like Radio Alhara, JamOnJamOnJamOnJam also serves as a temporary communal space to exercise active listening/listened, hosting/hosted, resonating/resonated, transmitting/transmitted, to jam on jam on jam on jam.

Over three days, JamOnJamOnJamOnJam hosted talks and had music jams in aka’s space. You can listen back to the audio recordings of all three days on Mixcloud.

Collectivity of collective sounds or how to jam together?

During documenta fifteen’s opening week, we invited the study group JamOnJamOnJamOnJam, which is composed of artists from the Global South and based in Amsterdam. JamOnJamOnJamOnJam is a series of jamming/gathering through sonic exchange by several residents on Radio Alhara. It started in the middle of lockdown in 2020 when the artists’ shared acoustic space became less accessible, this activity aimed to share the joy of jamming with friends and family beyond the acoustic space where the jamming takes place. Much like Radio Alhara, JamOnJamOnJamOnJam also serves as a temporary communal space to exercise active listening/listened, hosting/hosted, resonating/resonated, transmitting/transmitted, to jam on jam on jam on jam.

Over three days, JamOnJamOnJamOnJam hosted talks and had music jams in aka’s space. You can listen back to the audio recordings of all three days on Mixcloud.

Jam on Jam on Jam on Jam

تجميع الأصوات الجماعية أو كيفية التشويش معًا؟

تجميع الأصوات الجماعية أو كيفية التشويش معًا؟

قمنا خلال الأسبوع الافتتاحي لـ documenta 15، بدعوة مجموعة JamOnJamOnJamOnJam المؤلَّفة من فنانين من جنوب العالم ومقرها أمستردام. JamOnJamOnJamOnJam هي سلسلة قائمة على التجمع/العزف الجماعي من خلال التبادل الصوتي الذي قام به العديد من المشاركين في راديو الحارة. بدأ النشاط في منتصف فترة الحجر الصحّي في عام ٢٠٢٠ عندما غدا الوصول إلى المساحة الصوتية المشتركة للفنانين أقل سهولة، وكان يهدف إلى مشاركة متعة العزف مع الأصدقاء والعائلة خارج المساحة الصوتية المخصصة عادًة للعزف. كما راديو Alhara، يعمل JamOnJamOnJamOnJam أيضًا كمساحة مشتركة مؤقتة لممارسة السماع والإستماع، والإستضافة والإضافة، والتردد والتحويل والتحول من وإلى.

على مدى ثلاثة أيام ، استضافت مجموع JamOnJamOnJamOnJam محادثات وعزف موسيقي جماعي في فضاء aka. يمكنكم الاستماع مرّة أخرى إلى التسجيلات الصوتية للأيام الثلاثة كاملة على Mixcloud.

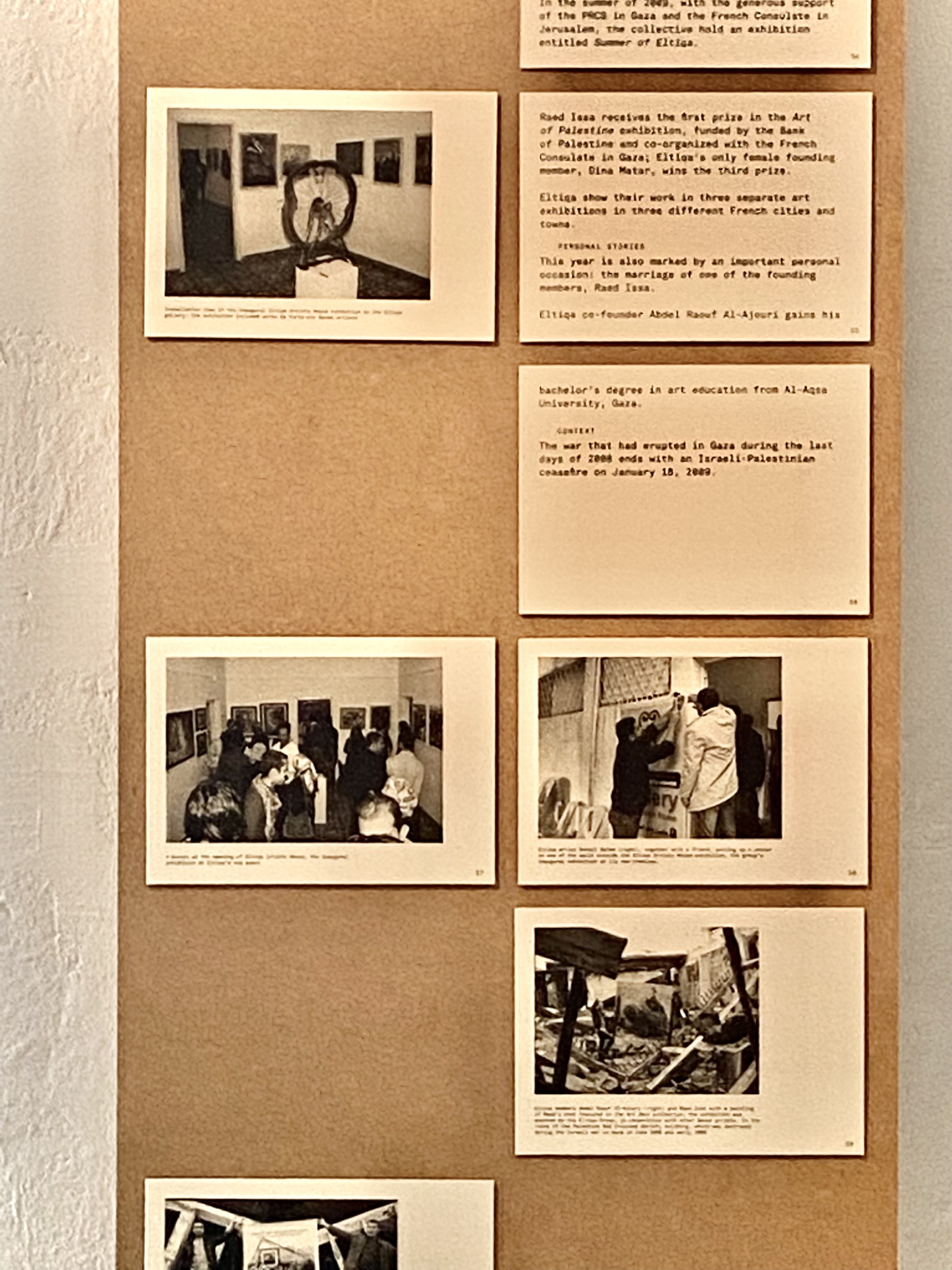

Hosting Eltiqa

Or what economic models can we learn from?

Eltiqa (Arabic for “meeting”) is an artist collective from Gaza city. For more than twenty years, they have developed artistic practices together and have extended their resources and knowledge to younger generations. What distinguishes Eltiqa as a collective are the flexible, creative, and responsive natures of their economic model, which helped the group to sustain itself through years of political, economic, and cultural struggles.

The group diversified its economic resources and responded in agility with the changing international funding landscape in Gaza. At times they relied on self-funding their project through selling their artworks, at other times they would rely on support from individuals and friends as well as external institutional funding bodies, many times combining those different survival mechanisms. When funding was not possible, they continued to run workshops themselves for younger artists depending on their own experience as resources. Many of the members of the group work full-time and part-time jobs in teaching and other fields and the members’ contribution to Eltiqa is volunteer-based. In a way, Eltiqa sustained their independence and sustainability, in the utmost way possible; without transforming Eltiqa into an institution, an NGO, or a commercial art entity. In this sense, inviting Eltiqa to be part of QoF was crucial to learn from, in order to disseminate their knowledge and expertise in working together and inventing their own economic model in one of the most unstable environments in the world.

In collaboration with them, the exhibition includes a selection of their artworks and photographs and an annotated timeline of their activities which we collected during our interviews with them. Through anecdotes collected by QoF, the timeline accentuates the different layers of their work and their practice’s correlation with political, social, economic, and personal stories. This is juxtaposed with the aesthetics of their artistic practice.

Eltiqa is formed by a group of seven artists: Mohammed Al Hawajri, Mohamed Abusal, Dina Matar, Rauf Alajouri, Raed Issa, Mohammed Dabous, and Sohail Salem who also have their individual art artistic practices to sustain along with the platform for younger artists they have created. Since 2002, the group has participated in many exhibitions locally and internationally; such as: ‘Gaza Seasons’ at L’Olivier Library in Geneva in 2007, ‘Eltiqa’s Summer’ at the Palestinian Red Crescent Society in Gaza in 2009, supported by the French Consulate in Jerusalem, and ‘Eltiqa in Ramallah’ in 2011 at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center, and at Galerie Arcima in Paris in 2010.

استضافة إلتقاء

أو أي النماذج الاقتصادية يمكننا التعلّم منها؟

"التقاء" مجموعة فنانين من مدينة غزة، ولأكثر من عشرين عاماً، طوّر فنانو وفنانات التقاء ممارسات فنية معاً ووسّعوا رقعة مواردهم ومعرفتهم لتصل إلى الأجيال الشابة. ما يميز التقاء كمجموعة هي الطبائع المرنة والإبداعية والمتجاوبة لنموذجها الاقتصادي، وهو ما ساعد المجموعة في الحفاظ على نفسها خلال سنوات من النضالات السياسية والاقتصادية والثقافية.

حرصت المجموعة على تنويع مواردها الاقتصادية واستجابت بمرونة مع مشهد التمويل الدولي المتغير في غزة. إذ اعتمدت في بعض الأوقات على التمويل الذاتي لمشاريعها من خلال بيع الأعمال الفنية خاصتها، وفي أوقات أخرى كانت تعتمد على الدعم من الأفراد والأصدقاء ناهيك عن هيئات التمويل المؤسسية الخارجية، وفي كثير من الأحيان تعمد إلى دمج شتّى آليات البقاء تلك. عندما كان التمويل متعذّراً، استمر الأعضاء في إدارة ورش العمل بأنفسهم للفنانين الشباب اعتمادًا على تجربتهم الخاصة فيما يخصّ الموارد. يعمل العديد من أعضاء المجموعة في وظائف بدوام كامل أو جزئي في مهنة التعليم ومجالات أخرى، كما تعتمد مساهمة الأعضاء في التقاء على العمل التطوعي. على نحوٍ ما ، حافظت التقاء على استقلاليتها واستدامتها بأقصى طريقة ممكنة، دون تحويل التقاء إلى مؤسسة أو منظمة غير حكومية أو كيان تجاري فني. بهذا المعنى، كانت دعوة التقاء للانضمام إلى مسألة التمويل أمرًا بالغ الأهمية للتعلم منه، وذلك لنشر معرفتهم وخبراتهم في العمل معًا وابتكار نموذج اقتصادي خاص بهم في واحدة من أكثر البيئات غير المستقرة في العالم.

بالتعاون معهم ، يتضمن المعرض مجموعة مختارة من أعمالهم الفنية وصورهم وجدولاً زمنيّاً مفصّلاً لأنشطتهم التي جمعناها خلال مقابلاتنا معهم. من خلال الحكايات التي جمعتها مؤسسة التمويل، يُبرز الجدول الزمني الطبقات المختلفة لعملهم وعلاقة ممارستهم بالقصص السياسية والاجتماعية والاقتصادية والشخصية. يقترن هذا الأمر بجماليات ممارستهم الفنية.

تتكون التقاء من مجموعة مؤلفة من سبعة فنّانين: محمد الحواجري، محمد أبوسل، دينا مطر، رؤوف العجوري، رائد عيسى، محمد دبّوس وسهيل سالم ولهم أيضًا ممارساتهم الفنية الفردية التي يجهدون في الحفاظ عليها جنبًا إلى جنب مع منصة الفنانين الشباب التي قاموا بخلقها.

شاركت المجموعة منذ عام ٢٠٠٢ في العديد من المعارض محليّاً ودولياًّ، مثل: "مواسم غزة" في مكتبة لوليفر في جنيف عام ٢٠٠٧، و"صيف التقاء" في جمعية الهلال الأحمر الفلسطيني في غزة عام ٢٠٠٩، بدعم من القنصلية الفرنسية في القدس، و "التقاء في رام الله" عام ٢٠١١ في مركز خليل السكاكيني الثقافي وفي جاليري Arcima بباريس عام ٢٠١٠.

Researchers: Yazan Khalili & Adèle Jarrar

Designer: Siwar Kraitem

Logistics: Ziad Haj Ali

Read an excerpt from an interview in which QoF member Yazan Khalili explains the overall approach to this project:

Designer: Siwar Kraitem

Logistics: Ziad Haj Ali

Read an excerpt from an interview in which QoF member Yazan Khalili explains the overall approach to this project:

الباحثون: يزن خليلي وأديل جرّار

التصميم: سوار قريطم

التجهيز اللوجستي: زياد حاج علي

التصميم: سوار قريطم

التجهيز اللوجستي: زياد حاج علي

تفضّلوا بقراءة مقتطف من مقابلة يشرح فيها عضو مسألة التمويل يزن الخليلي المقاربة العامّة لهذا المشروع:

“We approached our collaboration with Eltiqa as a research project. As Eltiqa was showing us work they had been creating, we brought our questions to the conversation. Were they creating political or apolitical art? Can apolitical art even come out of a place like Gaza? Lots of their work shown in Kassel is very playful, very colorful, which would seem to avoid the context of Gaza. Even the research presented alongside the works is sometimes just about the day-to-day issues of artists.

At the same time, these geopolitical questions are inescapable. In our research, we found lots of information about certain years and very little about others. And when we asked Eltiqa about the scarce years, they said, “Oh, this was after the war. For a year or two, we could not produce anything. We were too traumatized. Or we were thinking, ‘Why are we doing art now? Why make paintings that can be bombed and destroyed?’”

You can see how the political and artistic intertwine in, for example, Mohamed Abusal’s beautiful, colorful paintings of cactuses, which are especially interesting because the cactus is a very political plant in the Palestinian context. It was used to create a fence around houses. In many communities in Palestine that were destroyed after the Nakba, the only proof of existence was that the cacti grew back; they recreated the fences around destroyed houses.”

"لقد قاربنا تعاوننا مع التقاء كمشروع بحثي. بينما كانت "التقاء" تُظهر لنا العمل الذي كانوا يبدعونه، استحضرنتا أسئلتنا في المحادثة. هل كانوا يخلقون فنّاً سياسيّاً أم غير سياسي؟ هل يمكن للفن غير السياسي أن ينبثق من مكان مثل غزة؟ تبدو الكثير من أعمالهم المعروضة في كاسل مرحة وملونة للغاية، كما لو أنها تتجنب سياق غزة. حتى البحث المقدم إلى جانب الأعمال نراه يتعلق أحيانًا بالقضايا اليومية للفنانين.

في الوقت نفسه، لا مفرّ من هذه الأسئلة الجيوسياسية. وجدنا في بحثنا الكثير من المعلومات المتعلقة بسنوات معينة والقليل جدًا حول سنوات أخرى، وعندما سألنا التقاء عن السنوات الشحيحة، أجابوا: آه، كان هذا بعد الحرب. لمدة عام أو عامين، لم نتمكن من إنتاج أي شيء يُذكر. كنا مصدومين للغاية. أو بالأحرى كنا نفكر "لماذا الفن الآن؟ لماذا نخلق لوحات يمكن قصفها وتدميرها؟ "

يمكنك أن ترى كيف تشتبك الجوانب السياسية بالفنية، على سبيل المثال، في لوحات محمد أبوسال الجميلة والملونة للصبار، والتي تعتبر مثيرة للاهتمام بشكل خاص لأن الصبار هو نبات سياسي للغاية في السياق الفلسطيني. جرى استخدامه لإنشاء سور حول المنازل. في العديد من المجتمعات في فلسطين التي دمرت بعد النكبة، كان الدليل الوحيد على الوجود البيوت هو نبات الصبار الذي نما من جديد، وبفضله أعادوا بناء الأسوار حول البيوت المدمرة ".

During the opening week of documenta fifteen, The Question of Funding, along with Yazan Khalili and Adele Jarrar held a public talk in aka’s space with three members of Eltiqa, you can listen back to the conversation here.

Here are the stories and anecdotes the Question of Funding collected from Eltiqa and included in the exhibition in Kassel.

The harvest

Or how to extend knowledge beyond the limitation of the exhibition’s time and space?

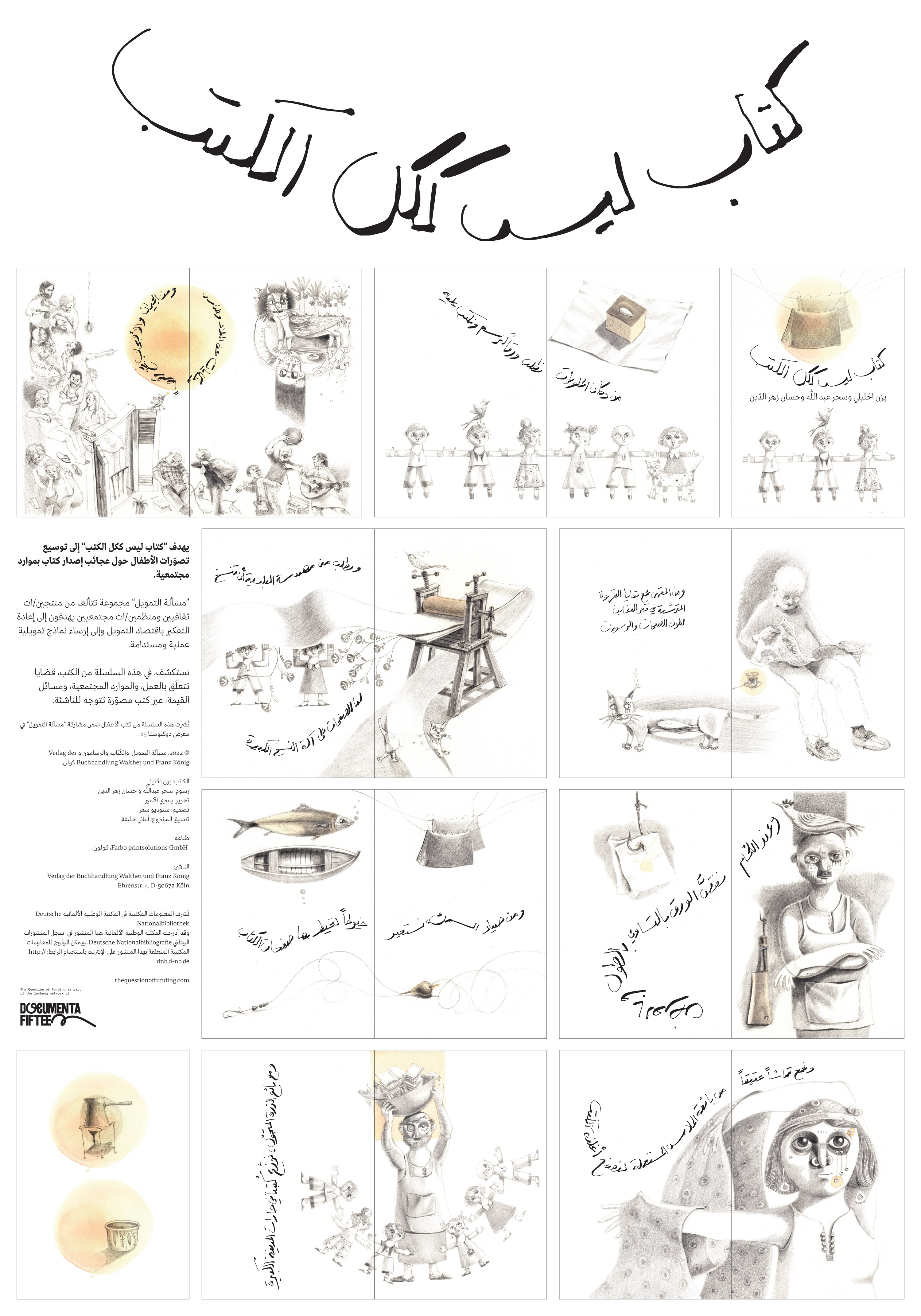

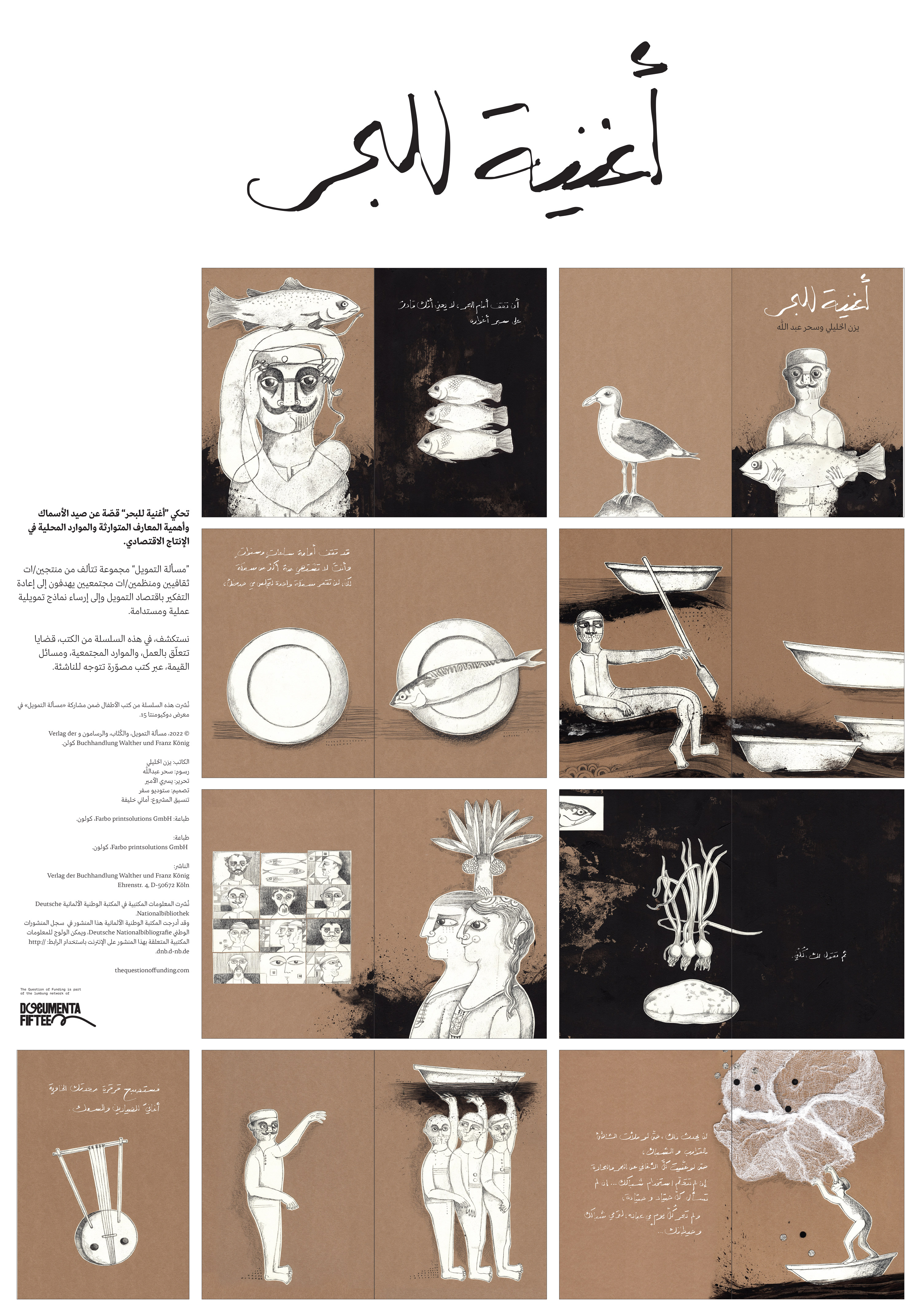

Another key project at documenta fifteen that reflects our questions on economic and human resources takes the form of four books in which we explore issues related to labor, communal resources, and value through illustrated stories addressed to a young readership.

In this context, we worked closely and collectively with artists, illustrators, writers, and translators from Palestine, Lebanon, and the diaspora to develop fictional stories and narratives that explore these questions. How does one explain labor and exchange to children or a general readership? How is the economy tied to the land and how can it harness existing resources in a place like Palestine?

We call these stories harvests because they, in fact, harvest from our earlier questions to deploy others. There aren’t many books that attempt to talk about the economy in our context and we think it is important to foster a collective imagination of what possible futures might hold.

الحصادأو كيف نوسّع المعرفة إلى ما هو أبعد من حدود زمان ومكان المعرض؟

يعكس مشروع رئيسي آخر في documenta 15 أسئلتنا حول الموارد الاقتصادية والبشرية متخذاً شكل أربعة كتب نستكشف فيها القضايا المتعلقة بالعمل والموارد المجتمعية والقيمة من خلال قصص مصورة موجهة إلى القراء الشباب.

في هذا السياق ، عملنا بشكل وثيق وجماعي مع فنانين ورسامين وكتّاب ومترجمين من فلسطين ولبنان والشتات لتطوير قصص وروايات خيالية تسبر هذه الأسئلة. كيف يشرح المرء العمل والتبادل للأطفال أو لعموم القرّاء؟ كيف يرتبط الاقتصاد بالأرض وكيف يمكنه تسخير الموارد الموجودة في مكان مثل فلسطين؟

نطلق على هذه القصص تسمية الحصاد لأنها تحصد فعلياً من أسئلتنا السابقة لتبثّ أسئلة أخرى. لا توجد الكثير من الكتب التي تسعى إلى التحدث عن الاقتصاد في سياقنا ونعتقد أنه من المهم تعزيز المخيلة الجماعية لما قد يحمله المستقبل المحتمل.

A Book Like No Other aims to expand children’s perceptions about the wonders of producing a book with communal resources.

يهدف "كتاب ليس ككل الكتب" إلى توسيع أفق تصورات الأطفال حول عجائب إنتاج كتاب باستخدام موارد مجتمعية.

Written by: Yazan Khalili

Edited by: Yousri Al Amir

Illustrated by: Sahar Abdallah

Translated to English by Mona Kareem

Translated to German by Larissa Bender

Arabic handwriting by Yazan Khalili

Design by studio safar

كتبه يزن الخليلي

حرره يسري الأمير

وضعت رسومه سحر عبد الله

ترجمته إلى الإنجليزية: منى كريم

ترجمته إلى الألمانية: لاريسا بيندر

كتابة يد يزن الخليلي وتصميم ستوديو سفر

Lina and the Working Hands: We use our hands daily, sometimes without us noticing them. Yet their lines bear the marks of time and labor. Lina, a defiant nine-year-old girl, decides to follow the journey of the working hands around her, from the market to the house and the fields.

نستخدم أيدينا بشكل يومي، حتى من دون أن ننتبه لها أحيانًا، ومع ذلك تحمل أيدينا آثر الزمن والعمل. تقرر لينا، الفتاة الجريئة التي تبلغ من العمر تسع سنوات، أن تلاحق رحلات الأيادي العاملة حولها، من السوق إلى البيت فالحقول.

Written by: Samir Skayni

Edited by: Yousri Al Amir

Illustrated by: Hatem Imam

Translated to English by Mona Kareem

Translated to German by Larissa Bender

Arabic handwriting by Yazan Khalili

Design by studio safar

كتبه سمير سكيني

حرره يسري الأمير

وضع رسومه حاتم الإمام

ترجمته إلى الإنجليزية: منى كريم

ترجمته إلى الألمانية: لاريسا بيندر

كتابة يد يزن الخليلي وتصميم ستوديو سفر

The Gentle Asphalt I Deserved is the journey of a shoe that travels between different owners and classes. The story explores how the shoe’s value changes from one geography to the next.

يأخذنا "إسفلت لطيف كان يليق بي!" في رحلة حذاء تنقّل عبر السنين بين أرجل أناس من طبقات إجتماعية مختلفة. ترينا القصة تغيّر قيمة الحذاء عند انتقاله من جغرافية إلى أخرى.

Written and edited by: Yousri Al Amir

Illustrated by: Hassan Zahredddine

Translated to English by Mona Kareem

Translated to German by Larissa Bender

Arabic handwriting by Yazan Khalili

Design by studio safar

كتبه يسري الأمير

وضع رسومه حسان زهر الدين

ترجمته إلى الإنجليزية: منى كريم

ترجمته إلى الألمانية: لاريسا بيندر

كتابة يد يزن الخليلي وتصميم ستوديو سفر.

The Song of the Sea: The book is a story about fishing and the importance of inherited knowledge and local resources in economic production.

يحكي "أغنية للبحر" قصّة عن صيد الأسماك وأهمية المعارف المتوارثة والموارد المحلية في الإنتاج الاقتصادي.

Written by: Yazan Khalili

Edited by: Yousri Al Amir

Illustrated by: Sahar Abdallah

Translated to English by Mona Kareem

Translated to German by Larissa Bender

Arabic handwriting by Yazan Khalili

Design by studio safar

كتبه يزن الخليلي

حرره يسري الأمير ووضعت رسومه سحر عبد الله

ترجمته إلى الإنجليزية: منى كريم

ترجمته إلى الألمانية: لاريسا بيندر

كتابة يد يزن الخليلي وتصميم ستوديو سفر

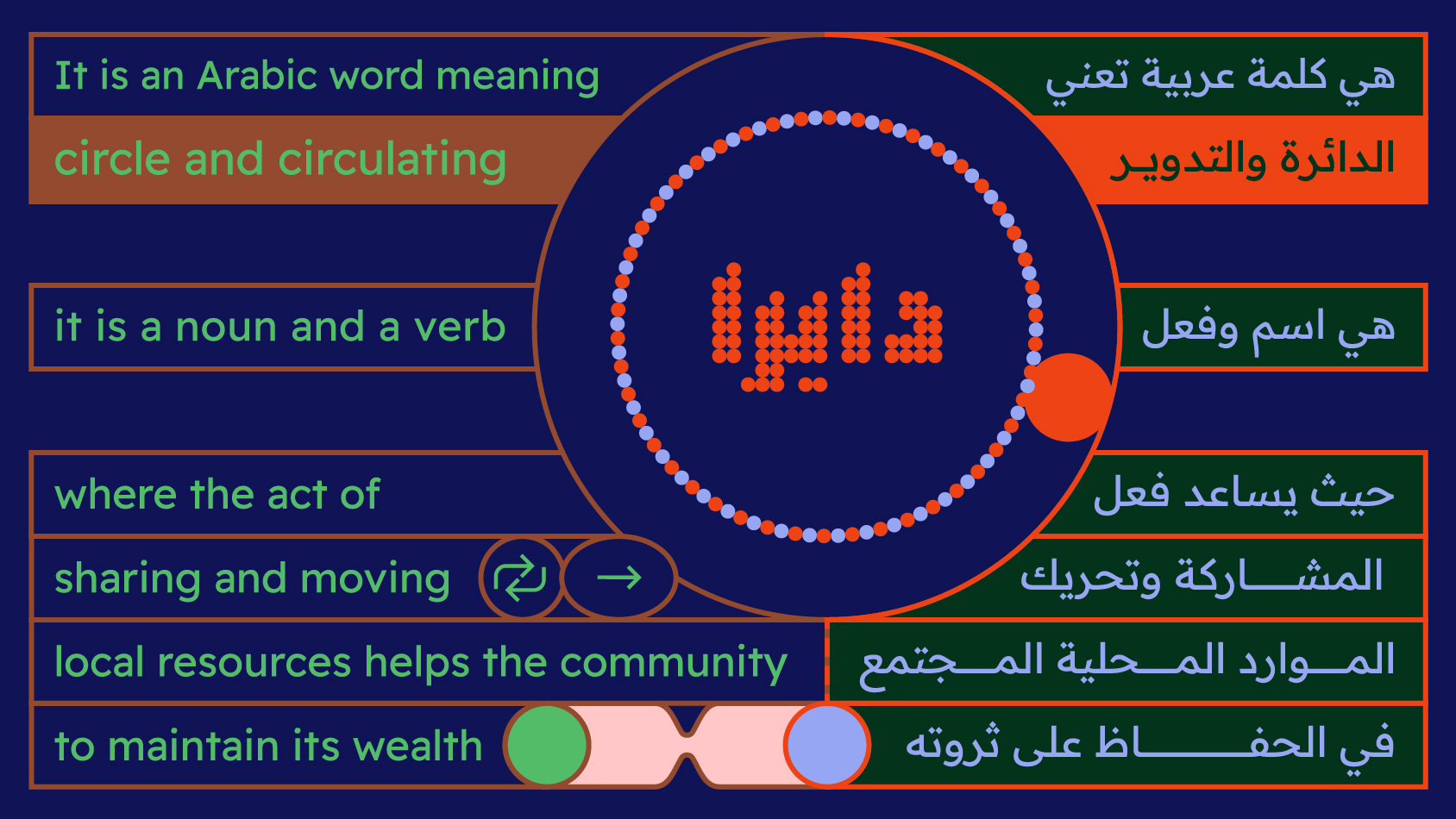

Dayra

or how to circulate communal economic value?

دايرا

أو كيف نعمم القيمة الاقتصادية المجتمعية؟

أو كيف نعمم القيمة الاقتصادية المجتمعية؟

In line with our ever-evolving questions and to better harness the vast resources that are continually stifled by the harsh economic and political realities in Palestine, our collective is building an economic model called Dayra, which is Arabic for “circle” and “circling”, that materializes existing trust circles within communities. It is a funding system that inverts the existing funding processes: it begins with zero budget and builds up community capital through the circulation of resources. This capital then becomes a local asset that stores value within the community.

Dayra will allow individuals, small businesses and organizations who are experiencing times of financial crises to make use of existing and future resources through trust systems based on blockchain technologies. This model expands on a community-governed economic system that will facilitate and connect local production from small cultural institutions, small businesses and creative industries, household economies, and freelancers to foster social development. This model not only aims to bypass the traditional and restrictive funding models that we have depended on so far but also aims to enlarge the trust circles ensuring a resilient and supplementary economy through which different communities in crisis are able to grow on their own terms.

Dayra was first introduced in the context of documenta fifteen in the form of posters and informative videos.

Dayra will allow individuals, small businesses and organizations who are experiencing times of financial crises to make use of existing and future resources through trust systems based on blockchain technologies. This model expands on a community-governed economic system that will facilitate and connect local production from small cultural institutions, small businesses and creative industries, household economies, and freelancers to foster social development. This model not only aims to bypass the traditional and restrictive funding models that we have depended on so far but also aims to enlarge the trust circles ensuring a resilient and supplementary economy through which different communities in crisis are able to grow on their own terms.

Dayra was first introduced in the context of documenta fifteen in the form of posters and informative videos.

بالتوازي مع أسئلتنا المتطورة باضطراد، ولتسخير الموارد الهائلة التي تخنقها الحقائق الاقتصادية والسياسية القاسية في فلسطين باستمرار، تعمل مجموعتنا على بناء نموذج اقتصادي يسمى دايرا، وهي كلمة عربية مشتقة من الـ"دائرة" والـ"دائري" التي تجسد دوائر الثقة القائمة داخل المجتمعات. إنه نظام تمويل يقلب عمليات التمويل الحالية: يبدأ بميزانية صفرية ويبني رأسمالاً مجتمعياً من خلال تداول الموارد، ثم يغدو رأس المال هذا أحد الأصول المحلية التي تختزن القيمة داخل المجتمع

ستتيح دايرا للأفراد والشركات الصغيرة والمنظمات ممن يعانون أوقاتاً عصيبة في الأزمات المالية الاستفادةَ من الموارد الحالية والمستقبلية من خلال أنظمة الثقة القائمة على تقنيات البلوكتشين. يتمدد هذا النموذج في نظام اقتصادي يحكمه المجتمع ومن شأنه تسهيل وربط الإنتاج المحلي المكوّن من المؤسسات الثقافية الصغيرة والشركات الصغيرة والصناعات الإبداعية والاقتصادات المنزلية وأصحاب الأعمال الحرة لتعزيز التنمية الاجتماعية. لا يهدف هذا النموذج إلى تجاوز نماذج التمويل التقليدية والمحصورة التي اعتمدنا عليها حتى الآن فحسب، بل يهدف أيضًا إلى توسيع دوائر الثقة لضمان اقتصاد مرن ومتكامل يمكن من خلاله لشتّى المجتمعات التي تمر بأزمة أن تنمو وفقاً لشروطها الخاصة

جرى تقديم دايرا بداية في سياق دوكومنتا 15 على شكل ملصقات وفيديوهات تعليمية

ستتيح دايرا للأفراد والشركات الصغيرة والمنظمات ممن يعانون أوقاتاً عصيبة في الأزمات المالية الاستفادةَ من الموارد الحالية والمستقبلية من خلال أنظمة الثقة القائمة على تقنيات البلوكتشين. يتمدد هذا النموذج في نظام اقتصادي يحكمه المجتمع ومن شأنه تسهيل وربط الإنتاج المحلي المكوّن من المؤسسات الثقافية الصغيرة والشركات الصغيرة والصناعات الإبداعية والاقتصادات المنزلية وأصحاب الأعمال الحرة لتعزيز التنمية الاجتماعية. لا يهدف هذا النموذج إلى تجاوز نماذج التمويل التقليدية والمحصورة التي اعتمدنا عليها حتى الآن فحسب، بل يهدف أيضًا إلى توسيع دوائر الثقة لضمان اقتصاد مرن ومتكامل يمكن من خلاله لشتّى المجتمعات التي تمر بأزمة أن تنمو وفقاً لشروطها الخاصة

جرى تقديم دايرا بداية في سياق دوكومنتا 15 على شكل ملصقات وفيديوهات تعليمية

What Is Dayra?

Dayra is a medium for circulating communal debt within existing trust circles. It allows inter-dependency between different economies in the society through measuring, sharing, and exchanging the value of their local resources as existing wealth in the absence of money.

Why Dayra?

Dayra is an Arabic word meaning circle and circulating, it is a noun and a verb, where the act of sharing, and moving local resources helps the community to maintain its wealth.

In line with the ever-evolving questions on economy and dependency, and to better harness the vast resources that are continually stifled by the political realities in Palestine and elsewhere in this extracted world, our growing collective is building an economic model that materializes existing trust circles within specific communities. The model starts with the premise that individuals, local organizations, cooperatives, and associations have no funds to sustain their operations but they have an abundance of resources of varying types, whether they are material, physical, and intellectual. The medium thus aims to generate and store value through the act of exchanging and putting to use local resources for the common good.

In line with the ever-evolving questions on economy and dependency, and to better harness the vast resources that are continually stifled by the political realities in Palestine and elsewhere in this extracted world, our growing collective is building an economic model that materializes existing trust circles within specific communities. The model starts with the premise that individuals, local organizations, cooperatives, and associations have no funds to sustain their operations but they have an abundance of resources of varying types, whether they are material, physical, and intellectual. The medium thus aims to generate and store value through the act of exchanging and putting to use local resources for the common good.

WHO IS DAYRA FOR?

Dayra is a tool to support deep locality. Individuals, small businesses, and local organizations who are living and existing within a local economy that share what we call a communal debt.

Below are some groups that dayra can be used as a medium of interdependence and circulation of communal debt. They are only an example of the first stage of the system, but can be expanded based on each locality.Individuals, small businesses, and local organizations who are living and existing within a local economy that share what we call a communal debt.

*Families

*Artists and educators

*Freelancers: translators, installers, graphic designers, farmers, service providers.

*Small studios: animation, graphic design, architecture, media, etc

*Small businesses: family and communal farms, family and small shops that sell local products, carpenters and blacksmiths, restaurants, clinics, hair dressers etc

*Local products manufacturers: food makers, soap makers, fabrics makers, etc

*Organizations: Cultural organizations, social support organizations, legal support, economical aid, health care organizations, agricultural support, etc

Below are some groups that dayra can be used as a medium of interdependence and circulation of communal debt. They are only an example of the first stage of the system, but can be expanded based on each locality.Individuals, small businesses, and local organizations who are living and existing within a local economy that share what we call a communal debt.

*Families

*Artists and educators

*Freelancers: translators, installers, graphic designers, farmers, service providers.

*Small studios: animation, graphic design, architecture, media, etc

*Small businesses: family and communal farms, family and small shops that sell local products, carpenters and blacksmiths, restaurants, clinics, hair dressers etc

*Local products manufacturers: food makers, soap makers, fabrics makers, etc

*Organizations: Cultural organizations, social support organizations, legal support, economical aid, health care organizations, agricultural support, etc

WHAT IS COMMUNAL DEBT?

Communal debt isn’t a credit or a debit, it’s not a financial value, but rather it is an unagreed upon understanding between certain community members that they need each other and support each other in different ways and manners to exist and survive in this world. Communal debt is a shared asset that lives within the community through different sectors and across different generations, it is a recognition of interdependency and trust, a paying forward system that strengthens the society's ability to go through hardships and stay prosperent against all odds.

WHAT WE ARE PUSHING AGAINST?

In the last 40 years, much of the world has been dominated by the neoliberal financial apparatus. One of the manifestations of that apparatus is that money has become the main measure of wealth in any given society, it has also become the main medium of exchanging resources. Financial crises are part of neoliberal economic cycles, they always put vulnerable communities in danger. When money becomes scarce it becomes harder for communities to fulfill their needs & exchange their existing local resources. But the absence of money doesn’t equate to the absence of resources, which are part of our communal wealth. These are human, material, natural & intellectual resources that exist despite their monetary values.

Financial crises are part of neoliberal economic cycles, they always put vulnerable communities in danger. When money becomes scarce it becomes harder for communities to fulfill their needs & exchange their existing local resources. But the absence of money doesn’t equate to the absence of resources, which are part of our communal wealth. These are human, material, natural & intellectual resources that exist despite their monetary values.

We are pushing towards bringing back the wealth to the people that generate it and help keep it within their societies.

Financial crises are part of neoliberal economic cycles, they always put vulnerable communities in danger. When money becomes scarce it becomes harder for communities to fulfill their needs & exchange their existing local resources. But the absence of money doesn’t equate to the absence of resources, which are part of our communal wealth. These are human, material, natural & intellectual resources that exist despite their monetary values.

We are pushing towards bringing back the wealth to the people that generate it and help keep it within their societies.

EXISTING MODELS WE LEARN FROM

The following models exist in Palestine, we take them as models to learn from and build upon:

Nuqoot: which means dripping. Maybe this is the oldest communal debt that keeps being paid from one generation to the next. It is used in weddings to support the newly weds to cover their expanses and it is expected that it is paid back to the next generation. It is an ongoing support system that everyone is expected to participate in.

The shop’s notebook: it is used in villages and small communities shops to allow residents to get stuff on the promise that they will pay back once they have money, it is based on the trust that the community members will always pay back what they got.

Jama’yeh (financial temporary coops): a saving system based on trust, when a group of people come together and agree that they will all put the same amount of money every beginning of a month in a common pot, and each one of them can take the whole amount at the beginning of the month on an agreed upon schedule depending on their needs. It is based on the trust that the ones who the receive the pot at the beginning will keep paying the amount in the later months. It is a system that allows people to save and receive big chunks of money without having to go to banks.

Al Oneh: is a support structure based on voluntary work one would do to support family, neighbors, and the society in general. It takes different forms and happens in different times, like when building a new house in a village, or preparing for an event (a wedding or a funeral), in the time of olive harvest, or moving heavy stuff. It is used in times of ease and prosperity, and also in times of hardships and austerity. it doesn't involve sharing money, but rather resources, effort, and time.

Nuqoot: which means dripping. Maybe this is the oldest communal debt that keeps being paid from one generation to the next. It is used in weddings to support the newly weds to cover their expanses and it is expected that it is paid back to the next generation. It is an ongoing support system that everyone is expected to participate in.

The shop’s notebook: it is used in villages and small communities shops to allow residents to get stuff on the promise that they will pay back once they have money, it is based on the trust that the community members will always pay back what they got.

Jama’yeh (financial temporary coops): a saving system based on trust, when a group of people come together and agree that they will all put the same amount of money every beginning of a month in a common pot, and each one of them can take the whole amount at the beginning of the month on an agreed upon schedule depending on their needs. It is based on the trust that the ones who the receive the pot at the beginning will keep paying the amount in the later months. It is a system that allows people to save and receive big chunks of money without having to go to banks.

Al Oneh: is a support structure based on voluntary work one would do to support family, neighbors, and the society in general. It takes different forms and happens in different times, like when building a new house in a village, or preparing for an event (a wedding or a funeral), in the time of olive harvest, or moving heavy stuff. It is used in times of ease and prosperity, and also in times of hardships and austerity. it doesn't involve sharing money, but rather resources, effort, and time.

Who is Dayra?

We are community members voracious for change in economic plight, who meet to discuss ideas of independence from the constraints of the existing economy, and the cultural practices that are resulting from this economy. The solution was an economic system that would facilitate and encourage local production such as agriculture and cultural production and make bridges in social development and unity using a blockchain medium that circulates economic value.

We are artists, cultural producers, academics, economics, blockchain architects, graphic and user experience designers, social activists, programers, and workers in different economical and productive fields.

We are artists, cultural producers, academics, economics, blockchain architects, graphic and user experience designers, social activists, programers, and workers in different economical and productive fields.

HOW DOES DAYRA WORK?

Dayra is a zero sum system, with every new member signing up, a certain amount of Dayras is created (lets say 1000 dayras). These Dayras remain in the main wallet of the system, divided into two pots: 1- the account of the member in the system (500 D). 2- the common pot (500 D).

In the member’s wallet, an equivalent amount in value of Validation points (VP) is created. (lets say 5 VP = 500 D).

VPs are the points through which a member can validate a certain act of sharing by another member, and therefore the system can release the agreed upon Dayras from the member’s account to their wallet. The VP is the representation of the communal debt that is shared once the member has on boarded.

Every time a VP is used it is deducted from the wallet and is stored in a locked wallet in the system.

There are 2 ways for the transactions to happen:

1- Validation / Release (Wallet to System to Wallet) : VP to Dayra

2- Direct transaction between wallets : Dayra to DayraCommon Pot can be accessed through communal voting on funds and share of resources. The community becomes the validator.

In the member’s wallet, an equivalent amount in value of Validation points (VP) is created. (lets say 5 VP = 500 D).

VPs are the points through which a member can validate a certain act of sharing by another member, and therefore the system can release the agreed upon Dayras from the member’s account to their wallet. The VP is the representation of the communal debt that is shared once the member has on boarded.

Every time a VP is used it is deducted from the wallet and is stored in a locked wallet in the system.

There are 2 ways for the transactions to happen:

1- Validation / Release (Wallet to System to Wallet) : VP to Dayra

2- Direct transaction between wallets : Dayra to DayraCommon Pot can be accessed through communal voting on funds and share of resources. The community becomes the validator.

HOW IT ALL STARTED?

Dayra started from a discussion about Muneh (an Arabic word which refers to a historical lavantian tradition of provisions for the future, within the discussion of The Question of Funding Collective (QOF) it came to mean the pot of resources). The idea was to invite different cultural institutions to share resources such as equipment, member’s skills, time…etc. Another set of events which propelled it were conditions faced during the pandemic in Palestine. Many daily workers in the service sector became unemployed. Simultaneously local Palestinain cultural institutions called for a meeting with funders to argue for an increase in funding because of the pandemic. A question propelled by those two ongoing crises was: why do cultural institutions see themselves outside of the wider economic crisis? We started to think of some kind of economical network which allows different economies in society to connect. While we - QoF - were trying to look for models we were also trying to find or to produce structures. as existing wealth in the absence of money.

While being members in the lumbung (documenta fifteen) our interest in ‘liberating’ money grew. In documenta fifteen others referred to it as transvestment, while we call it ‘liberation’ of money from one hegemonic system into another which liberates the money from donor conditions. It was an interest to return to the essence of money as a medium of exchange rather than a medium of speculation and financial industry. Neoliberal structures, such as finance, took over the practices of economy. We wanted to address the economy as a political practice. Economy is about interdependence. Money should not be wealth. The wealth of a community is the existing resources of a community. We saw money only as a medium of exchange rather than where wealth is stored.

We started by making assemblies with agricultural workers. When we started, compost was our medium of exchange. Slowly we discovered this might be limiting, so we started to do research on different forms of cooperatives around us. We also hosted colleagues and members in learning sessions on local currencies, focusing on how community currencies work.

While being members in the lumbung (documenta fifteen) our interest in ‘liberating’ money grew. In documenta fifteen others referred to it as transvestment, while we call it ‘liberation’ of money from one hegemonic system into another which liberates the money from donor conditions. It was an interest to return to the essence of money as a medium of exchange rather than a medium of speculation and financial industry. Neoliberal structures, such as finance, took over the practices of economy. We wanted to address the economy as a political practice. Economy is about interdependence. Money should not be wealth. The wealth of a community is the existing resources of a community. We saw money only as a medium of exchange rather than where wealth is stored.

We started by making assemblies with agricultural workers. When we started, compost was our medium of exchange. Slowly we discovered this might be limiting, so we started to do research on different forms of cooperatives around us. We also hosted colleagues and members in learning sessions on local currencies, focusing on how community currencies work.

WHAT ARE WE AND WHAT ARE WE NOT?

These are the principles, values, and issues we are still attempting to resolve. We hope that these might help inspire others:

1. Funding based on abundance instead of on scarcity

Dayra functions in a way where the community funds itself while circulating its resources. It self- funds with an abundance of resources.

2. Dayra is based on the circulation of communal debt

Dayra begins from a point of interdependencies. We are indebted to each other, when using Dayra we acknowledge this. We engage in a process of circulating debt. Debt becomes a communal resource; to be indebted to the community means you are part of it.

3. Non-trust based technology practiced within trust communal structures

We use the technology of the blockchain; a trustless tool. We are engulfing it with a community based governance system which is trust based. Using the technology as a medium for socially based infrastructure, the technology becomes only a tool.

4. Funding bottom up. Funds are produced by community sharing their existing resources (communal wealth)

Funds start from zero and build up by sharing resources. Value here is not for building assets, but rather for the act of sharing. What produces value is not assets but rather the sharing of the assets, its circulation within the community.

5. Circular by design

Members cannot accumulate Dayra. It is a medium of circulation and not accumulation. The structure is made so that Dayra is a medium for the continuous circulation of resources.

6. No accumulation of Dayra

If a member attempts to accumulate Dayra, they cannot use it anymore. Members have to keep sharing and using Dayra for it to maintain value.

7. Interdependency between different small economies

One of the aims of Dayra is to connect small and fragile economies together, because it is based on the diversity of economies (artists, freelancers, farmers…)

8. No inflation or deflation. Caps on wallets. Dayra is generated out of expanding members and ecosystem users

Dayra expands with every member, and declines along with their absence. One cannot accumulate a certain amount of Dayras, the relation between the Dayras in circulation and the ones available in the system is always equal. It cannot become a medium of derivatives and speculation. We cannot use financial policies on it, like what is happening now with money. It should remain a very basic medium of exchange.

9. Minting the act of sharing, value based on circulation. Dayra is not an NFT

Value is produced from the act of sharing, it is not an asset in itself. We are not trying to create NFTs, which produce value for digital assets. Dayra is not an NFT in the sense that we are trying to produce value for the communal exchange processes.

10. Local wealth and extraction: keeping local wealth within the community. One can’t use Dayra outside of its local ecosystem

Every ecosystem can create its own Dayra, it is not our aim that it is globally used. We would be extracting wealth if we do that. Dayra should give value to communal wealth, if we transfer this to other stronger economies Dayra will disappear into that wealth. Through Dayra we attempt to circulate local resources and avoid investing in imported goods, as this is wealth which will leave the community. It is also about encouraging local ecosystems in supporting each other, especially in times of hardship.

11. Validation points as a way to communicate to the shared wealth

The system is divided into two point systems: Dayra and validation points. Validation points are the debt received when a member joins Dayra. Those validation points are in the communal pot already, what members can do is to transfer them, or validate someone else’s act of sharing through one’s points. Validation points are a declaration of the communal debt. Through points systems, individuals are able to communicate with the common pot.

12. Governance moves from a centralized system towards a decentralized system

Dayra is a centralized system. It starts with governance by members of the Dayra working group or QoF while slowly building tools it will transform into decentralized governance, involving all members.

13. Issues of arbitration and disagreements?

Part of what QoF is trying to deal with within the social systems section of Dayra application, is about how to disagree and how to create models and ways of finding resolutions. We are trying to find a way of how the larger community can intervene to solve issues.

14. It is not Crypto, it is not currency, it is not a coin…pushing blockchain outside of the fin-tech

We are using blockchain technology in Dayra. Blockchain has lost its potential, as crypto currencies are used to reproduce speculative economies but with a different technology. We return to the basics and promise of what blockchain can give us. We don’t treat Dayra as a national currency, because it is not. We’re trying to use other basic terms, such as points, units, tokens, or simply just Dayra.

1. Funding based on abundance instead of on scarcity

Dayra functions in a way where the community funds itself while circulating its resources. It self- funds with an abundance of resources.

2. Dayra is based on the circulation of communal debt

Dayra begins from a point of interdependencies. We are indebted to each other, when using Dayra we acknowledge this. We engage in a process of circulating debt. Debt becomes a communal resource; to be indebted to the community means you are part of it.

3. Non-trust based technology practiced within trust communal structures

We use the technology of the blockchain; a trustless tool. We are engulfing it with a community based governance system which is trust based. Using the technology as a medium for socially based infrastructure, the technology becomes only a tool.

4. Funding bottom up. Funds are produced by community sharing their existing resources (communal wealth)

Funds start from zero and build up by sharing resources. Value here is not for building assets, but rather for the act of sharing. What produces value is not assets but rather the sharing of the assets, its circulation within the community.

5. Circular by design

Members cannot accumulate Dayra. It is a medium of circulation and not accumulation. The structure is made so that Dayra is a medium for the continuous circulation of resources.

6. No accumulation of Dayra

If a member attempts to accumulate Dayra, they cannot use it anymore. Members have to keep sharing and using Dayra for it to maintain value.

7. Interdependency between different small economies

One of the aims of Dayra is to connect small and fragile economies together, because it is based on the diversity of economies (artists, freelancers, farmers…)

8. No inflation or deflation. Caps on wallets. Dayra is generated out of expanding members and ecosystem users

Dayra expands with every member, and declines along with their absence. One cannot accumulate a certain amount of Dayras, the relation between the Dayras in circulation and the ones available in the system is always equal. It cannot become a medium of derivatives and speculation. We cannot use financial policies on it, like what is happening now with money. It should remain a very basic medium of exchange.

9. Minting the act of sharing, value based on circulation. Dayra is not an NFT

Value is produced from the act of sharing, it is not an asset in itself. We are not trying to create NFTs, which produce value for digital assets. Dayra is not an NFT in the sense that we are trying to produce value for the communal exchange processes.

10. Local wealth and extraction: keeping local wealth within the community. One can’t use Dayra outside of its local ecosystem

Every ecosystem can create its own Dayra, it is not our aim that it is globally used. We would be extracting wealth if we do that. Dayra should give value to communal wealth, if we transfer this to other stronger economies Dayra will disappear into that wealth. Through Dayra we attempt to circulate local resources and avoid investing in imported goods, as this is wealth which will leave the community. It is also about encouraging local ecosystems in supporting each other, especially in times of hardship.

11. Validation points as a way to communicate to the shared wealth

The system is divided into two point systems: Dayra and validation points. Validation points are the debt received when a member joins Dayra. Those validation points are in the communal pot already, what members can do is to transfer them, or validate someone else’s act of sharing through one’s points. Validation points are a declaration of the communal debt. Through points systems, individuals are able to communicate with the common pot.

12. Governance moves from a centralized system towards a decentralized system

Dayra is a centralized system. It starts with governance by members of the Dayra working group or QoF while slowly building tools it will transform into decentralized governance, involving all members.

13. Issues of arbitration and disagreements?

Part of what QoF is trying to deal with within the social systems section of Dayra application, is about how to disagree and how to create models and ways of finding resolutions. We are trying to find a way of how the larger community can intervene to solve issues.

14. It is not Crypto, it is not currency, it is not a coin…pushing blockchain outside of the fin-tech

We are using blockchain technology in Dayra. Blockchain has lost its potential, as crypto currencies are used to reproduce speculative economies but with a different technology. We return to the basics and promise of what blockchain can give us. We don’t treat Dayra as a national currency, because it is not. We’re trying to use other basic terms, such as points, units, tokens, or simply just Dayra.