WHAT IS THE QUESTION OF FUNDING?

Since the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993, cultural institutions and organizations working in Palestine experienced a shift in the way they practiced and engaged their local communities. In this new era, they had to formalize and register as NGOs to receive international funding necessary for their operations, activities, and running expenses. This form of funding cemented a type of institutional infrastructure whereby individuals working in arts and culture, agriculture and social activism in Palestine (and elsewhere) became totally reliant on this model and consequently on the institutions themselves to subsist and to continue practicing. To borrow a term from agriculture, these funding practices led to a monoculture of cultural institutions.

These infrastructures have thus far faced more financial burdens but also political conditions imposed by foreign or international donors. They also rely exclusively on financial funding as the only means to support cultural or communal practices. Through the NGO model, this extreme dependence on the donor economy caused concern and frustration among those who worked in them but we were interested in how collective and affirmative critiques or actions against this status-quo could be materialized or practiced. In asking about the question of funding, we also prompted other relevant debates around issues of accountability, politics, the economy and health of the community, as well as cultural work at large.

As a discursive inquiry, the question of funding brought to the fore crucial issues we had been asking ourselves and each other, some of which relate to the political nature of the donor economy; economic infrastructures and how they instate types of cultural practice; cultural and knowledge production in Palestinian society; and the cyclical crises that organizations continue to face today.

The question of funding thus aims to rethink and critique the donor economy in its present configuration whilst finding ways out of the political, economic, and cultural paradigms that it has created over the years. It is not about refusal of funding but about finding different modalities and resources, whether they are monetary, material or intellectual, with which we can grow within our communities and localities.

Since the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993, cultural institutions and organizations working in Palestine experienced a shift in the way they practiced and engaged their local communities. In this new era, they had to formalize and register as NGOs to receive international funding necessary for their operations, activities, and running expenses. This form of funding cemented a type of institutional infrastructure whereby individuals working in arts and culture, agriculture and social activism in Palestine (and elsewhere) became totally reliant on this model and consequently on the institutions themselves to subsist and to continue practicing. To borrow a term from agriculture, these funding practices led to a monoculture of cultural institutions.

These infrastructures have thus far faced more financial burdens but also political conditions imposed by foreign or international donors. They also rely exclusively on financial funding as the only means to support cultural or communal practices. Through the NGO model, this extreme dependence on the donor economy caused concern and frustration among those who worked in them but we were interested in how collective and affirmative critiques or actions against this status-quo could be materialized or practiced. In asking about the question of funding, we also prompted other relevant debates around issues of accountability, politics, the economy and health of the community, as well as cultural work at large.

As a discursive inquiry, the question of funding brought to the fore crucial issues we had been asking ourselves and each other, some of which relate to the political nature of the donor economy; economic infrastructures and how they instate types of cultural practice; cultural and knowledge production in Palestinian society; and the cyclical crises that organizations continue to face today.

The question of funding thus aims to rethink and critique the donor economy in its present configuration whilst finding ways out of the political, economic, and cultural paradigms that it has created over the years. It is not about refusal of funding but about finding different modalities and resources, whether they are monetary, material or intellectual, with which we can grow within our communities and localities.

These infrastructures have thus far faced more financial burdens but also political conditions imposed by foreign or international donors. They also rely exclusively on financial funding as the only means to support cultural or communal practices. Through the NGO model, this extreme dependence on the donor economy caused concern and frustration among those who worked in them but we were interested in how collective and affirmative critiques or actions against this status-quo could be materialized or practiced. In asking about the question of funding, we also prompted other relevant debates around issues of accountability, politics, the economy and health of the community, as well as cultural work at large.

As a discursive inquiry, the question of funding brought to the fore crucial issues we had been asking ourselves and each other, some of which relate to the political nature of the donor economy; economic infrastructures and how they instate types of cultural practice; cultural and knowledge production in Palestinian society; and the cyclical crises that organizations continue to face today.

The question of funding thus aims to rethink and critique the donor economy in its present configuration whilst finding ways out of the political, economic, and cultural paradigms that it has created over the years. It is not about refusal of funding but about finding different modalities and resources, whether they are monetary, material or intellectual, with which we can grow within our communities and localities.

THE COLLECTIVE

OR

WHO IS ASKING THE NOW:

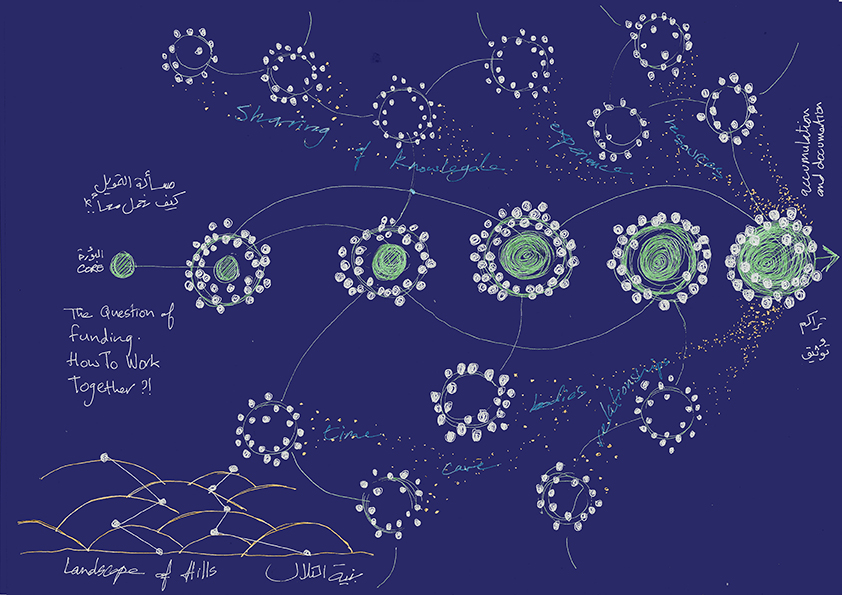

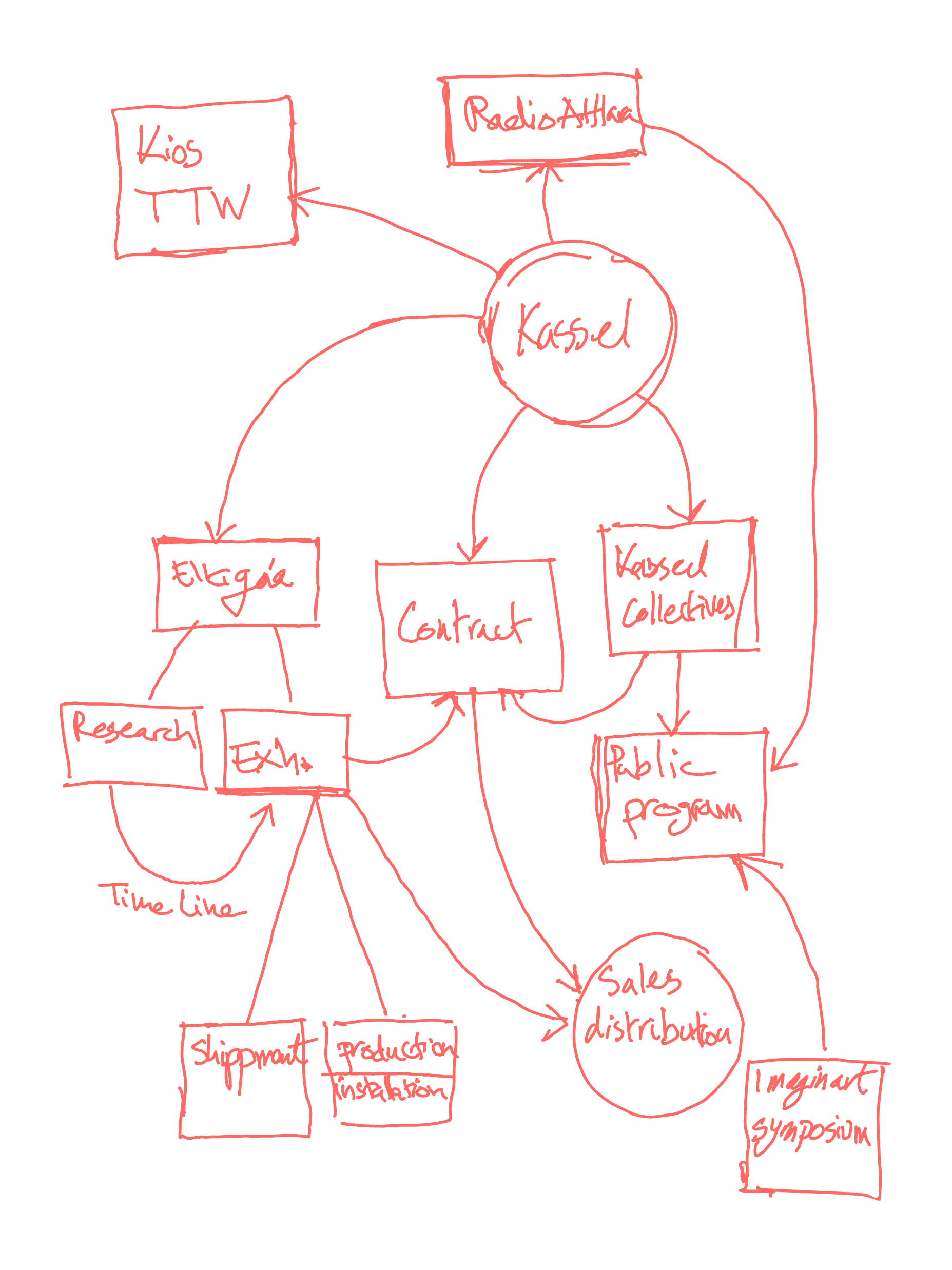

Since the question of funding has been festering among local practitioners and organizers in Palestine for some time, we first came together informally as individuals from different groups, collectives, NGOs and institutions in different localities and began to hold several meetings that took place at the garden of Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center in 2019.

During these meetings and workshops, we charted questions, ideas, and experiences and explored debates and problems that related to the overarching question of funding in Palestine. After a number of us committed to these meetings, we became a collective composed of artists, cultural workers, and activists.

The Question of Funding became a framework for us to think on how we can work together to propose economic models that reduce dependency on the donor economy and reinforce the existing solidarity between people and organizations.

Within our collective, we are committed to changing the way we work on and think about cultural production and its funding mechanisms. In our projects, we prioritize the process itself and shift our positions as cultural practitioners to focus on infrastructure: how art and culture can liberate themselves from the economic infrastructure of the traditional institution and how to make use of the rich resources that exist in Palestinian society today.