How to work togetherكيف نعمل معا?What did we do in documenta fifteenماذا فعلنا في دوكيومنتا خمسة عشر? What is dayra ما هي دايرا?

The QoF in documenta fifteen

OUR FIRST PUBLIC MOMENT, OR IS IT?

Since we were a very young collective when documenta approached us to take part in its fifteenth edition and despite our initial hesitations to commit to such an endeavor, the projects we presented there reflect both the conceptual and theoretical vectors that emerged from our ongoing debates and discussions on the question of funding, economic infrastructures, as well as knowledge production.

Our presence in documenta fifteen took the form of four different projects that were activated in various ways both locally in Kassel and beyond the framework of the 100 days of the exhibition.

The lumbung, which brought together hundreds of collectives and thousands of individuals both before and during documenta fifteen, proposed a unique structure within which we deployed our processes, invited friends and collaborators, and thought and worked together around issues at the core of our practice.

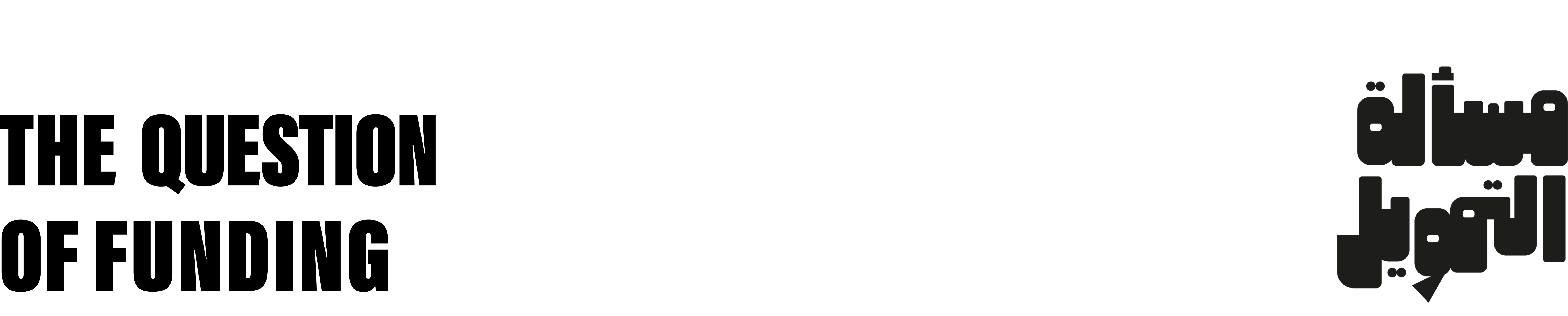

Poster by Nour Hifaoui

Welcome to Aka

Or how to connect to a context?

As a collective in the lumbung and in documenta fifteen, we wanted to work against the usual patterns imposed by big artistic institutions and biennials that typically invite artists and cultural workers to produce works, exhibit them and swiftly leave without having engaged the city and its residents.

In the spirit of the lumbung, we opened one of our spaces in documenta fifteen to other local collectives who were working on their diverse projects and within their own communities. As such, we engaged in long discussions with several Kassel-based collectives and organizations who shared a common goal: to secure a permanent space for their programs and activities. In WH22, the abandoned building we shared with other documenta fifteen artists, they came together to create aka, a decentralized network of self-organizing and grassroots collectives and open space for concerts, workshops, performances, exhibitions, discussions, and more.

As invited artists, we become hosts to other local guests. They host their activities in our space and we use their space to host our own. The connection with aka extends the map of relations, almost like ripples in a pond that widen the circles of individuals, ideas, and potentials.

Jam on Jam on Jam on Jam

Collectivity of collective sounds or how to jam together?

During documenta fifteen’s opening week, we invited the study group JamOnJamOnJamOnJam, which is composed of artists from the Global South and based in Amsterdam. JamOnJamOnJamOnJam is a series of jamming/gathering through sonic exchange by a fewsome residents on Radio Aalhara. It started in the middle of lockdown in 2020 when the artists’ shared acoustic space became less accessible, this activity aimed to share the joy of jamming with friends and family beyond the acoustic space where the jamming takes place. Much like Radio Aalhara, JamOnJamOnJamOnJam also serves as a temporary communal space to exercise active listening/listened, hosting/hosted, resonating/resonated, transmitting/transmitted, to jam on jam on jam on jam.

Over three days, JamOnJamOnJamOnJam hosted talks and had music jams in aka’s space.

Collectivity of collective sounds or how to jam together?

During documenta fifteen’s opening week, we invited the study group JamOnJamOnJamOnJam, which is composed of artists from the Global South and based in Amsterdam. JamOnJamOnJamOnJam is a series of jamming/gathering through sonic exchange by a fewsome residents on Radio Aalhara. It started in the middle of lockdown in 2020 when the artists’ shared acoustic space became less accessible, this activity aimed to share the joy of jamming with friends and family beyond the acoustic space where the jamming takes place. Much like Radio Aalhara, JamOnJamOnJamOnJam also serves as a temporary communal space to exercise active listening/listened, hosting/hosted, resonating/resonated, transmitting/transmitted, to jam on jam on jam on jam.

Over three days, JamOnJamOnJamOnJam hosted talks and had music jams in aka’s space.

Hosting Eltiqa

Or what economic models can we learn from?

Eltiqa (Arabic for “meeting”) is an artist collective from Gaza city. For more than twenty years, they have developed artistic practices together and have extended their resources and knowledge to younger generations. What distinguishes Eltiqa as a collective are the flexible, creative, and responsive natures of their economic model, which helped the group to sustain itself through years of political, economic, and cultural struggles.

The group diversified its economic resources and responded in agility with the changing international funding landscape in Gaza. At times they relied on self-funding their project through selling their artworks, at other times they would rely on support from individuals and friends as well as external institutional funding bodies, many times combining those different survival mechanisms. When funding was not possible, they continued to run workshops themselves for younger artists depending on their own experience as resources. Many of the members of the group work full-time and part-time jobs in teaching and other fields and the members’ contribution to Eltiqa is volunteer-based. In a way, Eltiqa sustained their independence and sustainability, in the utmost way possible; without transforming Eltiqa into an institution, an NGO, or a commercial art entity. In this sense, inviting Eltiqa to be part of QoF was crucial to learn from, in order to disseminate their knowledge and expertise in working together and inventing their own economic model in one of the most unstable environments in the world.

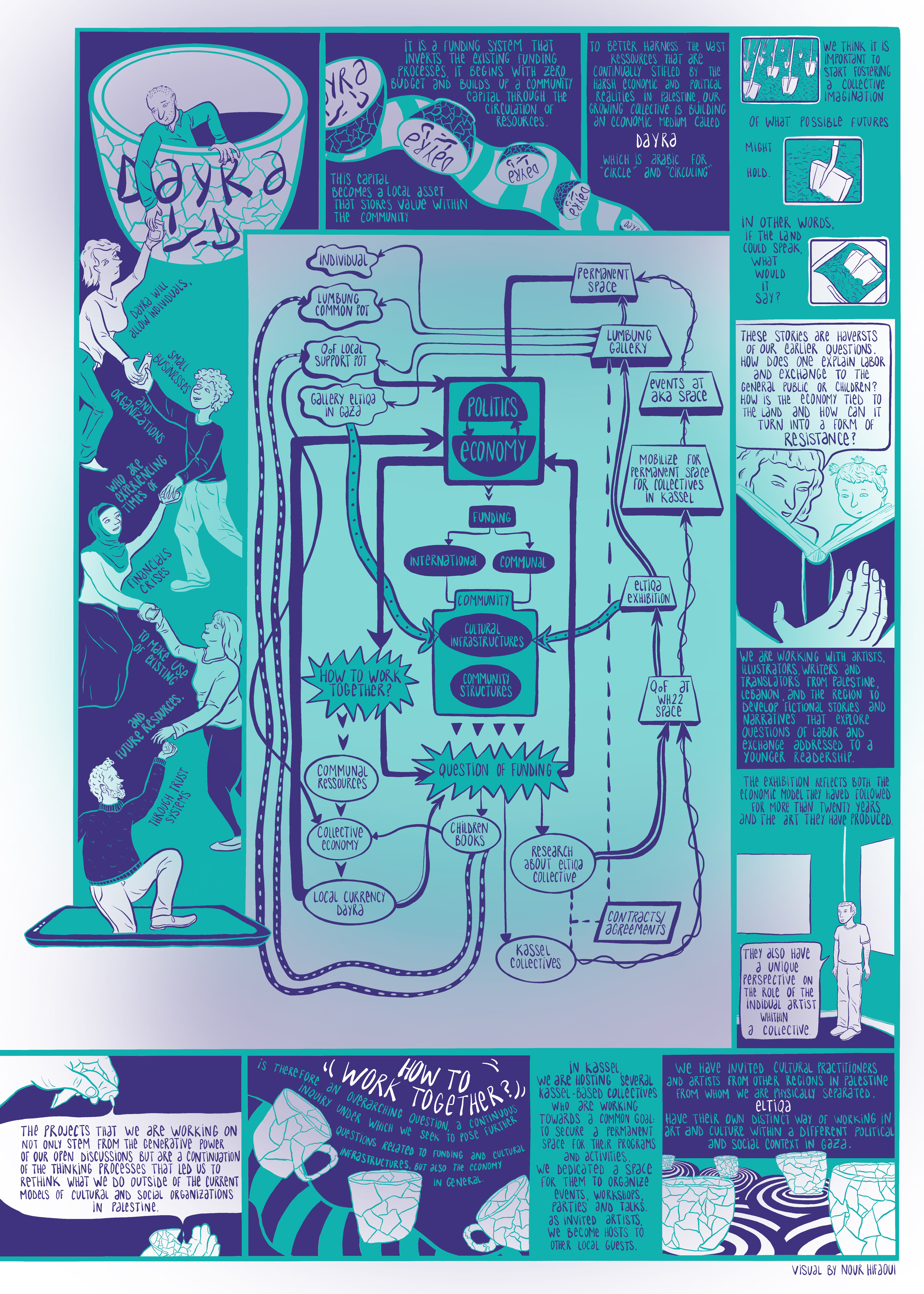

In collaboration with them, the exhibition includes a selection of their artworks and an annotated timeline of their activities. Through anecdotes by the collective and research by QoF, the timeline accentuates the different layers of their work and their practice’s correlation with political, social, economic, and personal stories. This is juxtaposed with the aesthetics of their artistic practice.

Eltiqa is formed by a group of seven artists: Mohammed Al Hawajri, Mohamed Abusal, Dina Matar, Rauf Alajouri, Raed Issa, Mohammed Dabous, and Sohail Salem who also have their individual art artistic practices to sustain along with the platform for younger artists they have created. Since 2002, the group has participated in many exhibitions locally and internationally; such as: ‘Gaza Seasons’ at L’Olivier Library in Geneva in 2007, ‘Eltiqa’s Summer’ at the Palestinian Red Crescent Society in Gaza in 2009, supported by the French Consulate in Jerusalem, and ‘Eltiqa in Ramallah’ in 2011 at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center, and at Galerie Arcima in Paris in 2010.

Read an excerpt from an interview in which QoF member Yazan Khalili explains the overall approach to this project:

“We approached our collaboration with Eltiqa as a research project. As Eltiqa was showing us work they had been creating, we brought our questions to the conversation. Were they creating political or apolitical art? Can apolitical art even come out of a place like Gaza? Lots of their work shown in Kassel is very playful, very colorful, which would seem to avoid the context of Gaza. Even the research presented alongside the works is sometimes just about the day-to-day issues of artists.

At the same time, these geopolitical questions are inescapable. In our research, we found lots of information about certain years and very little about others. And when we asked Eltiqa about the scarce years, they said, “Oh, this was after the war. For a year or two, we could not produce anything. We were too traumatized. Or we were thinking, ‘Why are we doing art now? Why make paintings that can be bombed and destroyed?’”

You can see how the political and artistic intertwine in, for example, Mohamed Abusal’s beautiful, colorful paintings of cactuses, which are especially interesting because the cactus is a very political plant in the Palestinian context. It was used to create a fence around houses. In many communities in Palestine that were destroyed after the Nakba, the only proof of existence was that the cacti grew back; they recreated the fences around destroyed houses.”

The works on display are for sale as part of the Lumbung gallery and will support Eltiqa artists, their space and ecosystem, while also contributing to the Lumbung collective pot.

Below are selections from the stories and anecdotes we collected from Eltiqa and included in the exhibition in Kassel:

The Smaller the Fund

The more flexible grants are the most useful, according to what they told us. In 2008, they received an unconditional grant amounting to 50,000 USD, which guaranteed their survival. The group was able to independently manage the grant for over six years, to cover the rent of the space, organize several exhibitions, support the production of artworks for non-members, and cover daily transportation expenses over that time. It enabled them to establish the Eltiqa gallery as an open art space during a very difficult period for them as individuals who had lost their jobs within the difficult context in Gaza immediately after the Israeli assault of 2008–2009.

Another Type of Art Dealer: Smuggling Paint into Gaza

The Israeli occupation bans the entry of several food items and other goods into Gaza. Banned items include sage, jam, chocolate, fried potatoes, fabric, notebooks, flower vases, and toys. Cinnamon, plastic buckets, and combs are allowed. Under these odd and unjustified constraints, it is hard to find good quality art materials in Gaza such as canvas, paint, and paintbrushes, etc. Mohamed Abusal tells us that this does not change the expectations of art collectors that the Eltiqa artists will use high-quality materials to produce their artworks. This leads the artists to rely on their relationships with friends and international organizations to smuggle art supplies from Jerusalem and elsewhere into Gaza so they can make their paintings. Often, artists ask collectors to pay them in art supplies instead of money for their participation in art exhibitions. Abusal also tells us that Eltiqa helps young artists by giving them free art materials so they can produce high-quality works to be able to sell them outside of Gaza.

The Political Non-Political Art

In one of our conversations, Al-Hawajri told us that he uses vibrant colors and apolitical stories in his artworks because since the beginning of his artistic career he wanted to make art for art’s sake. He wished to produce and depict colorful and perhaps fictional memories, in contrast to the political reality. However, although his and the group's practise was founded around a slogan similar to “art for art’s sake,” their artworks are often interpreted through a political lens, particularly when exhibited outside of Palestine. They told us that a political reading is always projected unto their work, regardless of whether they intended it or not. That is how “the other” sees them: as politicized bodies from a politically charged area.

Questions on an Interdependent Wellness

They told us that the Eltiqa gallery spaces have multiple uses. Sometimes they are used as private studios for them to work on their own personal projects, while at other times they are used as open spaces for hosting cultural activities and exhibitions. These seemingly contradictory uses of the space as both private and public provoke endless debate among the founding members. Do we turn the space into our own private studios to use whenever we need? Or do we keep it as a private/public space? These discussions can take up much time and energy, which affects the intensity and frequency of the programming targeting the wider community.

The harvest

Or how to extend knowledge beyond the limitation of the exhibition’s time and space?

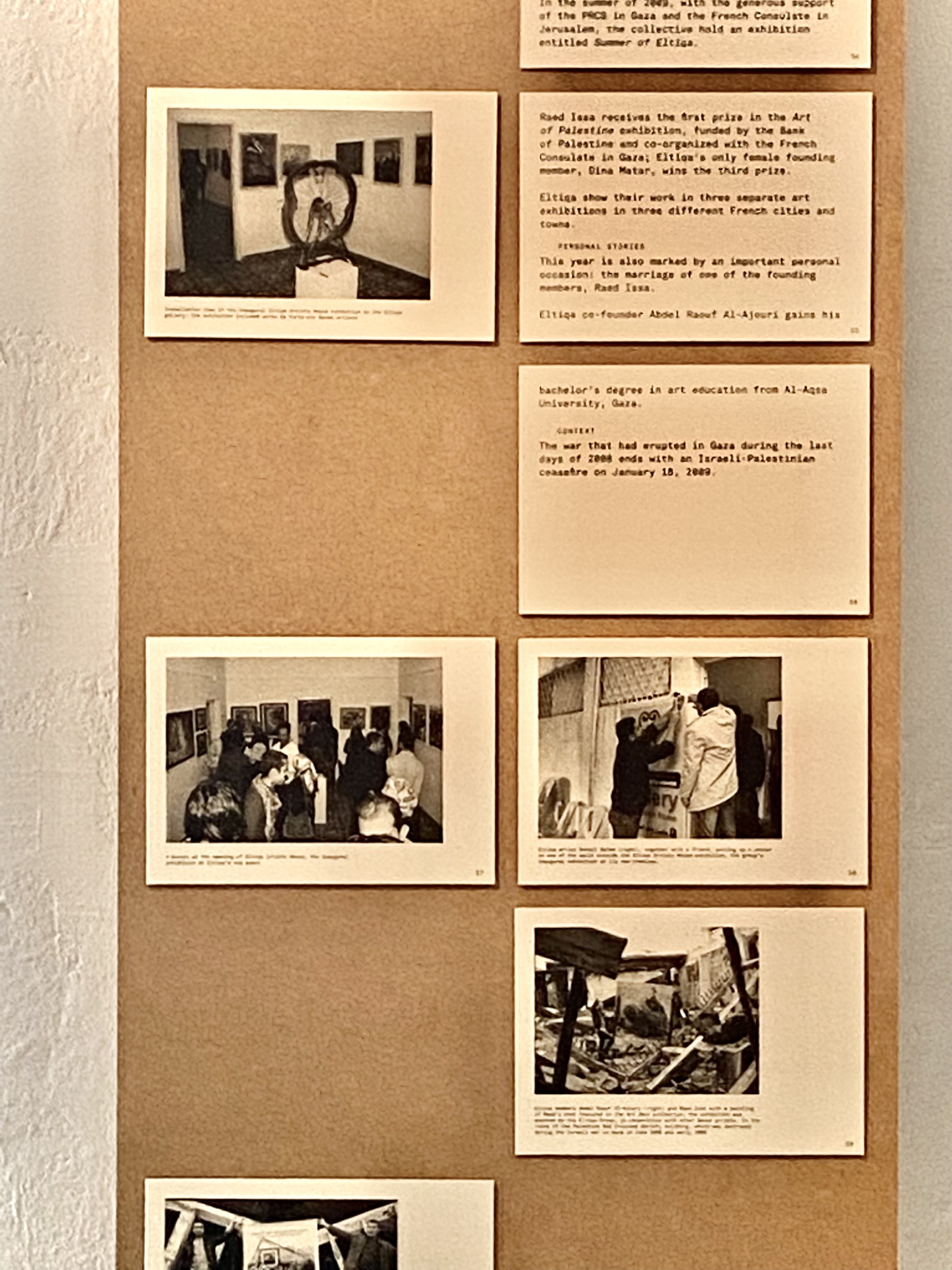

Another key project at documenta fifteen that reflects our questions on economic and human resources takes the form of four books in which we explore issues related to labor, communal resources, and value through illustrated stories addressed to a young readership.

In this context, we worked closely and collectively with artists, illustrators, writers, and translators from Palestine, Lebanon, and the diaspora to develop fictional stories and narratives that explore these questions. How does one explain labor and exchange to children or a general readership? How is the economy tied to the land and how can it harness existing resources in a place like Palestine?

We call these stories harvests because they, in fact, harvest from our earlier questions to deploy others. There aren’t many books that attempt to talk about the economy in our context and we think it is important to foster a collective imagination of what possible futures might hold.

A Book Like No Other aims to expand children’s perceptions about the wonders of producing a book with communal resources.

![]()

Written by: Yazan Khalili

Edited by: Yousri Al Amir

Illustrated by: Sahar Abdallah

Translated to English by Mona Kareem

Translated to German by Larissa Bender

Arabic handwriting by Yazan Khalili

Design by studio safar

Written by: Yazan Khalili

Edited by: Yousri Al Amir

Illustrated by: Sahar Abdallah

Translated to English by Mona Kareem

Translated to German by Larissa Bender

Arabic handwriting by Yazan Khalili

Design by studio safar

Lina and the Working Hands: We use our hands daily, sometimes without us noticing them. Yet their lines bear the marks of time and labor. Lina, a defiant nine-year-old girl, decides to follow the journey of the working hands around her, from the market to the house and the fields.

![]()

Written by: Samir Skayni

Edited by: Yousri Al Amir

Illustrated by: Hatem Imam

Translated to English by Mona Kareem

Translated to German by Larissa Bender

Arabic handwriting by Yazan Khalili

Design by studio safar

Written by: Samir Skayni

Edited by: Yousri Al Amir

Illustrated by: Hatem Imam

Translated to English by Mona Kareem

Translated to German by Larissa Bender

Arabic handwriting by Yazan Khalili

Design by studio safar

The Gentle Asphalt I Deserved is the journey of a shoe that travels between different owners and classes. The story explores how the shoe’s value changes from one geography to the next.

![]()

Written and edited by: Yousri Al Amir

Illustrated by: Hassan Zahredddine

Translated to English by Mona Kareem

Translated to German by Larissa Bender

Arabic handwriting by Yazan Khalili

Design by studio safar

Written and edited by: Yousri Al Amir

Illustrated by: Hassan Zahredddine

Translated to English by Mona Kareem

Translated to German by Larissa Bender

Arabic handwriting by Yazan Khalili

Design by studio safar

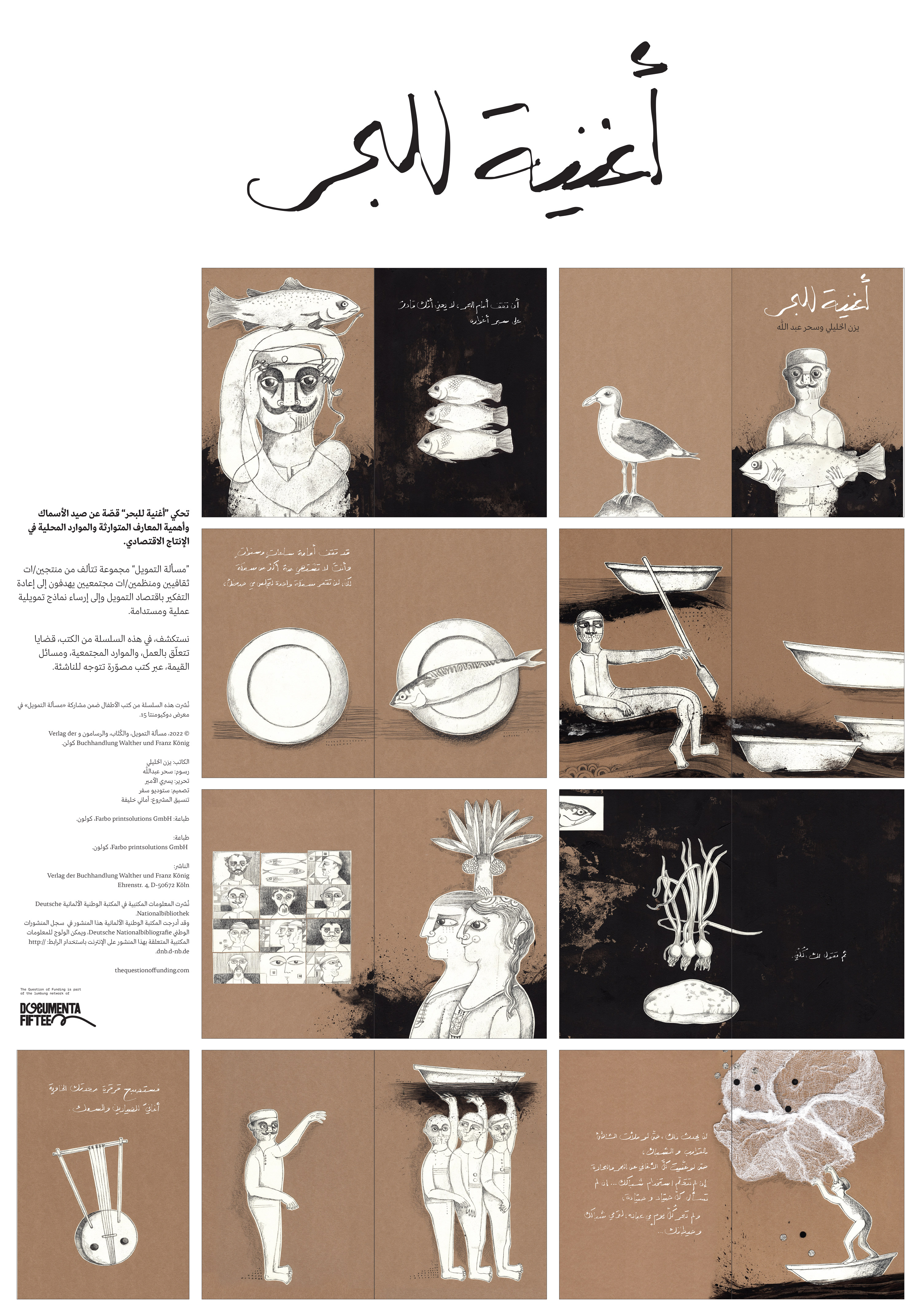

The Song of the Sea: The book is a story about fishing and the importance of inherited knowledge and local resources in economic production

![]()

Written by: Yazan Khalili

Edited by: Yousri Al Amir

Illustrated by: Sahar Abdallah

Translated to English by Mona Kareem

Translated to German by Larissa Bender

Arabic handwriting by Yazan Khalili

Design by studio safar

Written by: Yazan Khalili

Edited by: Yousri Al Amir

Illustrated by: Sahar Abdallah

Translated to English by Mona Kareem

Translated to German by Larissa Bender

Arabic handwriting by Yazan Khalili

Design by studio safar

Dayra

Or how do we liberate the money?

In line with our ever-evolving questions and to better harness the vast resources that are continually stifled by the harsh economic and political realities in Palestine, our collective is building an economic model called Dayra, which is Arabic for “circle” and “circling”, that materializes existing trust circles within communities. It is a funding system that inverts the existing funding processes: it begins with zero budget and builds up community capital through the circulation of resources. This capital then becomes a local asset that stores value within the community.

Dayra will allow individuals, small businesses and organizations who are experiencing times of financial crises to make use of existing and future resources through trust systems based on blockchain technologies. This model expands on a community-governed economic system that will facilitate and connect local production from small cultural institutions, small businesses and creative industries, household economies, and freelancers to foster social development and unity. This model not only aims to bypass the traditional and restrictive funding models – we call it “liberating the money” – that we have depended on so far but also aims to enlarge the trust circles to ensure a resilient and supplementary economy through which different communities in crisis are able to grow on their own terms.

Dayra is a medium for circulating communal economic value, asupplementary economy that generates value through minting existing resources and maintaining wealth within the community.

To know more about Dayra, visit its website here

Bibliography

Many of the reflections, frustrations, and critiques that contributed to the formation of The Question of Funding also exist in different forms and languages with several interlocutors. The bibliography below charts some of the thinking processes that helped shape the work of the collective today. It includes texts by and interviews with members of our collective but also texts by other authors and thinkers that encourage us to think more deeply about the topics that we engage. We hope this list grows with time and you are welcome to recommend to us texts, videos, interviews that you think we should look into:

READING CORNER

On institutional practices and navigating crises

Khaldi, Lara, Khalili, Yazan. “What we talk about when we talk about crisis: A conversation part I”. Interview by Marwa Arsanios. E-flux. 2020

Khaldi, Lara, Khalili, Yazan. “What we talk about when we talk about crisis: A conversation part II”. Interview by Marwa Arsanios. E-flux. 2022

On cultural institutions

Khalili, Yazan. “The Total Work of the Cultural Institution”. Interview by Rayya Badran. Makhzin. 2020.

Khalili, Yazan. “The Institution as Ideology”. A-desk. 2020

On institutional practices and navigating crises

Khaldi, Lara, Khalili, Yazan. “What we talk about when we talk about crisis: A conversation part I”. Interview by Marwa Arsanios. E-flux. 2020

Khaldi, Lara, Khalili, Yazan. “What we talk about when we talk about crisis: A conversation part II”. Interview by Marwa Arsanios. E-flux. 2022

On cultural institutions

Khalili, Yazan. “The Total Work of the Cultural Institution”. Interview by Rayya Badran. Makhzin. 2020.

Khalili, Yazan. “The Institution as Ideology”. A-desk. 2020

دعاء علي، شاكر جرّار. "المؤسسات المالية الدولية، والمديونية، والحرب: مقابلة مع علي القادري". حبر.2019

LISTENING CORNER

Khalefa, Amany. “The Question of Funding – with Amany Khalifa''. Interview. Conducted by Errant Podcast. March 24, 2022

Khalefa, Amany. “The Question of Funding – with Amany Khalifa''. Interview. Conducted by Errant Podcast. March 24, 2022

الخليلي، يزن و شرقاوي، فيروز. تحديات التمويل

وتأثيرها في الثقافة الفلسطينية مؤسسة الدراسات الفلسطينية

إيمان حموري. 2021